Pentecost, 1987: the Reichstag Building was the backdrop for three nights of concerts by world famous acts. Genesis – with Phil Collins – Eurythmics, and David Bowie performed in light of the 750th anniversary of the city of Berlin. At least 60,000 West Berlin residents attended the concert. Another several thousand East Berliners tried to get as close as possible to the Brandenburg Gate, on the border of East and West, to be able to hear some of the concert. From a distance, they listened to David Bowie sing ‘We can be heroes, just for one day’.

The first two concerts were peaceful enough. The East German gathering at Brandenburg Tor wasn’t a demonstration yet. “All I wanted was to be close to those super stars just once in my life,” one of the visitors would say years later. The third night, however, the atmosphere turned grim. Out of the blue, a mass protest ensued with demonstrators chanting ‘Die Mauer muss weg, weg, weg’, and ‘Gorbi, Gorbi!’ Riots broke out later that night, which were crushed by police. Hundreds of people were arrested.

The Reichstag concerts are now considered a pivotal moment of civil disobedience, as those nights have contributed to a group of people finding the courage to start a revolution in 1989.

“Only many years later did I feel I should have done more. It was just that I thought I’d retire in the GDR,” says historian Ilko Sascha Kowalczuk (1967), born in East Berlin. For years now, he’s been researching the GDR, and how civilians tried to show their dissatisfaction with the system.” Kowalczuk continues: “Had I known it would all fall apart in 1989, I’d have taken to the streets every day. I would have accepted one hundred years in prison. I just didn’t know.”

It starts in your childhood: you grow up with an all-consuming fear, says Kowalczuk. “You know exactly what you can’t talk about with your parents, and what topics are off-limits at school. There are rules as to what you should look like, and what TV channels you watch. You keep quiet, because you might end up in prison otherwise. And my mother didn’t speak for fear of my being taken away from her.” It didn’t happen, but that fear was instilled in all children, he explains. “Which was very convenient for those in power. Everyone was sure the Stasi was everywhere and omnipresent, when they obviously weren’t, of course.”

In a system with so many rules, civil disobedience starts with opposing those rules. “You’d notice people starting to break certain laws at some point.”The GDR expert remembers making an anti-communist remark at school when he was fifteen years old. “The teacher didn’t like that one bit, and our entire class was denied recess. We were forced to listen to his story about the successes of the GDR, and why I was an idiot.” After that, Kowalczuk had a problem, not because of what he’d said, but because he had ruined his classmates’ recess. “Most people obeyed the rules not only out of fear, but they didn’t want to be a nuisance to their peers, either.”

When he was fifteen, Kowalczuk decided to stop ‘playing along’. He didn’t want to follow the path his communist father had set out for him. In hindsight, it may not have been a deliberate choice at all. “I wanted to breathe. It was only when the system responded with all kinds of measures that I thought to myself: okay, so I’m an enemy.”

It had far-reaching consequencing for Kowalczuk: he wasn’t allowed to graduate or go to university. Instead, he went to trade school to become a construction worker. “But I didn’t feel like working in construction at all, as it seemed far too strenuous.” He found a job as a doorman at a small institute in southern Berlin. “It was pretty common for people like me to become a gardener at a cemetary or doorman. Insignificant positions. Wages were measly, but at least the state let you be: ‘Right, we get it, you don’t want to have anything to do with us. As long as you refrain from demonstrating, we’ll leave you alone then.’” After the Wall fell, Kowalczuk was finally free to go to university, where he started researching the GDR. “I certainly didn’t plan to have my career revolve around GDR research, but things happen.”

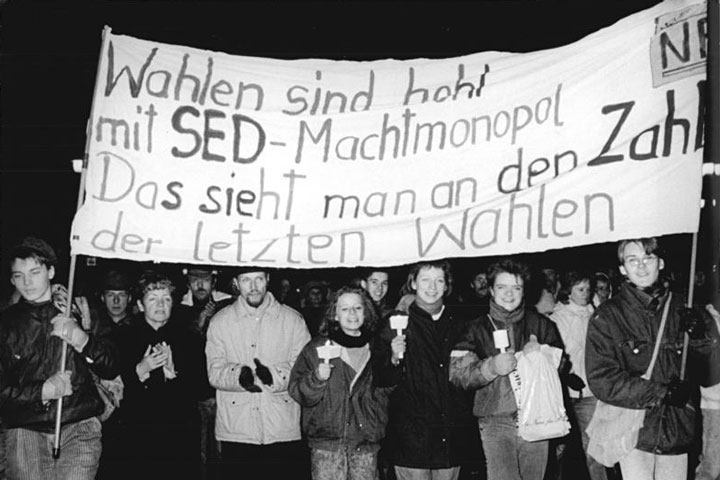

There wasn’t a major political opposition in the last decade of the GDR, according to Kowalczuk. “The Stasi claimed it was only a few thousand people, but you have to be careful with numbers like that.” He does realize it involved a realtively small group. “The group of people who tried to show their civil disobedience is much larger, of course,” says the historian. He mentions the youths at concerts screaming the Wall should be taken down, Union fans chanting ‘Stasi Schweine’ during matches against BFC Dynamo, teenagers who weren’t allowed to attend university because they refused to join the army, and the people who suddenly converted to Christianity. But things are never as black-and-white as they seem, Kowalczuk stresses: “Hardly anyone is always the same person. One day you oppose the system, the next you conform. The day after that, you do both.” He gives an example: “I’d vent my opinion in the afternoon, only to shut up later that night because I was scared they’d throw me in jail. The next morning I’d be embarrassed I kept schtum.”