Halfway through our conversation, in the middle of a sentence, Visinel Balan (1987) can no longer contain himself: “This is my first day as a father!” His son was born the night before. Yet, here Visinel is – on a Saturday barely twelve hours after having looked his son in the eyes for the first time – in a stuffy room with a dropped ceiling in a remote industrial park in Bucharest. The small, sweltering room is the office of his foundation Desenăm Viitorul Tău, Draw your Own Future, which supports orphans.

“Cold,” he answers when he is asked what it feels like to be a father. “I try hard not to be influenced. I’m afraid of getting too attached to people.” With an almost triumphant look as if to prove that he is faster than his conversation partner, he adds: “And yes, of course, that has to do with my past.” He continues in a serious tone: “But when I saw him for the first time yesterday – in a room full of babies, him being the only quiet one – I suddenly had to cry.” It mainly feels strange, he says. “I don’t know what maternal love is – or paternal love, for that matter. It made me think of Adam and Eve. They had a child but didn’t know what to do with it; nobody had ever shown them. Still, together they discovered love. It has to be something like that.”

“This is my first day as a father. I’m afraid of getting too attached to people”

Visinel Balan was one of the estimated 100,000 children who grew up in an ‘orphanage’ around 1989. Nicolae Ceauşescu had just taken office as leader of the Romanian Communist Party when he announced a decree designed to ensure population growth. Abortion became illegal for women under 45, parents without children received fines, the marriageable age was lowered from 18 to 15, and the sale and production of contraceptives were banned. This way, Ceauşescu hoped to build a great communist nation and a large army. Bringing a child to the world was like a gift to the country.

Ceauşescu’s children

Visinel Balan’s mother gave birth to as many as fourteen babies. Ceauşescu's decree soon produced a population surplus. At the same time, his economic policy led to empty stores and a shortage of everything. Many families were too poor to take care of their children; their ‘surplus’ ended up in huge state orphanages. Balan, too, was delivered to such an orphanage two months after his birth.

Daniel Rucareanu (40) was six when he ran away from home because his stepfather abused him incessantly, he explains while sitting at a small table in the back corner in the courtyard of a cafe in Bucharest. As a little boy, he lived on the street for some time – ‘that was tough but much better than back home’ – until September 1985 when he wound up, eight years old, in an orphanage through child protective services. In that public institution in Ploiești Town, he lived together with 100 children. After one year and a half, he was moved to another institution in Bușteni. There were 400 other children living there.

The first day, he learned an important lesson, he says. “I was overwhelmed by the noise of the huge number of close-packed children, and by the penetrating odour. A mixture of dirty clothes and urine. That first day, I was beaten by a boy. He was bigger, so he hit me. The children would beat others because they themselves were beaten by other children. That day, I learned what life was like in an orphanage: you have no protection, anyone can hurt you.” He remembers a few deaths. “A boy who could play the harmonica. He fell from a window. Another little boy drowned in the Black Sea when we were there during the summer. There were more cases like that.”

When in 1989 the Iron Curtain was lifted, and Nicolae Ceauşescu was executed on Christmas Day, the world knew little of what had happened in the isolated Romania all those years. In 1990 ‘Ceauşescu’s children’ became world news. Horrified, the Western media showed the images of naked, emaciated children who were locked up together as beasts in prison-like institutes. Countless Americans and Western Europeans offered to become adoptive parents, and many foundations went to Romania to provide help. Romania was put under pressure from abroad: the country had to take care of its children.

Model country

Until the end of the 1990s very little changed. “I had no idea what I had started,” Andy Guth tells us. In 1990, as a young Romanian paediatrician with hardly any experience, he was suddenly appointed director of a large orphanage for children under four. “The managers had all left; everyone was afraid of what would happen after the revolution. I had never been a member of the Communist Party and I knew nobody in that region: that made me the ideal candidate.”

“You could say that not just the children were institutionalised but the employees as well,” Guth continues. 400 babies and toddlers lived in the home; they hardly had any toys or room to play, and often twenty children were crammed into one room, he remembers. “De staff treated the children as objects. With a few exceptions, they did not show any empathy or compassion. They spent an remarkable amount of time on drinking coffee and smoking cigarettes.” The staff was had had medical training, but social workers or pedagogues were absent: these kinds of studying fields did not exist in Romania, like in many other Eastern Bloc countries in the seventies.

Aid agencies and NGOs vigorously tried to make improvements throughout the 1990s, which did result in some reforms, but only when the European Union began to exert pressure in the beginning of 2000, things really started to change. The EU warned Romania: if the country did not make rapid progress, it could forget about becoming a member of the EU. The threat was effective. New laws were hastily made with the help of foreign foundations and experts. The Romanian government made an ambitious promise: by 2020 all large children's homes would be closed. Later, the deadline was adjusted to 2022.

The numbers are impressive: in 2000, about 100,000 children were living in large orphanages, in 2016 this number had dropped to 8,000. Also, about 50 thousand children now grow up in kinship care, foster homes or small group homes. Due to the rapid improvements and the great ambitions, Romania became the model for other countries, especially former Soviet states, where child protection was also abominable.

Spotless hallways and tightly-made beds

In a bare living room, Leo is surrounded by as many as three women; he has their undivided attention. The boy – eighteen years old, although his appearance suggests he is much younger – is doing an exercise with a Lego car. The women clap hard. ‘Well done! Well done!’ Leo has autism, an intellectual disability and behavioural problems, Cătălina Tabarcea explains. She is the manager of two small group homes in Bucharest. The facility is brand new: spotless hallways and rooms with tightly-made beds, most of them ostentatiously provided with one stuffed animal. Bare but tidy, with paper stars on the ceiling. Four years ago, 110 children were living here; now there are eight to twelve children per apartment.

Out of nowhere, a boy – a man almost – begins to cry silently. Counsellor Cristina Haivas puts her arm around him; he hides his face in her chest. “Ramon is always anxious and restless, really,” she explains. “Abandoned as a baby, he grew up in an institution. Of course, now he has more space, and there are more people to help him but the years that were crucial for his development have gone by.” The boy keeps holding her hand the entire conversation.

In his sweltering office, Visinel Balan laughs scornfully. “Of course you will only see the facilities the government wants you to see. Romania as a model for other countries? Give me a break. Children are still physically and sexually abused in the system, and disabled children still die.” Two years ago, research from the Romanian NGO Centre for Legal Resources (CRJ) revealed that around 4,500 disabled people – children and adults – had passed away in institutions between 2010 and 2014. The case of Valentin Câmpeanu, an 18-year-old disabled boy who died in an institution, became notorious. In 2014, the European Court of Human Rights ruled that the Romanian state was liable for his death due to lack of appropriate medical care, adequate accommodation and sufficient food. In 2015, the United Nations expressed concern about the inhuman conditions in which disabled children in Romania are cared for. They mentioned neglect, malnutrition, lack of medical and psychological treatment – resulting in death. In the context of the care for healthy children, scandals about physical or sexual abuse frequently emerge as well, but large-scale research into this problem has not yet been done.

Since Romania joined the EU, the reforms have been on the back burner. To shake things up, Balan started a ‘fight against the system’ in which he constantly tries to draw attention to individual cases of abuse and neglect. Consequently, Balan has become a ‘persona non grata’ for many institutions– they simply do not let him inside any longer. Now he tries to stir things up through politics, as an advisor to a member of parliament. In another attempt to speed up the deinstitutionalisation, as the closure of the large orphanages is called in proper caregivers jargon, he recently offered a petition to the Ministry of Justice.

Apologies from the government

At the small table in the cafe’s courtyard with cheerful coloured lights, Daniel Rucareanu dejectedly shakes his head. He has serious doubts about the quality and effects of the Romanian reforms, he says. But while Balan tries to improve the situation for today’s ‘children of the system’, Rucareanu focuses on the past. With his NGO, he wants to bring about a large parliamentary inquest into the abuses in the Ceauşescu orphanages from the 1960s to the early 1990s. “And an apology from the government for all the violence and misery that the state has caused with its system of care.” He makes procedural requests from local authorities to view the institutions' archives, he writes articles, and lobbies with politicians.

Rucareanu cannot let go of the past. When he was 14, he left the orphanage where he had lived for years. It felt as if he had ‘unlearned how to be human’, he explains. “I had lost my ability to talk to other people. I had trouble standing upright.” For a moment, he looks up from the table where his eyes had been focused up to that point. Almost immediately he lowers his gaze again. It is the only time he faintly smiles: “I still don’t dare to look people in the eye.”

“I had unlearned how to be human. I had trouble standing upright.”

Daniel Rucareanu is an exception with his university education – just like Visinel Balan. Most children of the system do not turn out alright. The chance that they will become unemployed, homeless, depressed, criminals or victims of human trafficking is much greater than it is with ‘normal’ children. Rucareanu’s NGO is called Federeii for good reason: it means something like 'place full of garbage'. And the garbage must be cleaned up, he thinks. “I have read a lot about the Holocaust in recent years. I am impressed with the way the Jews deal with the past. Their suffering is described to the last detail. They realise that the past – no matter how terrible – is worth investigating and remembering; after all, it is part of who they are. In my country, on the other hand, there is no respect for the ordinary man's suffering.”

Changing approach

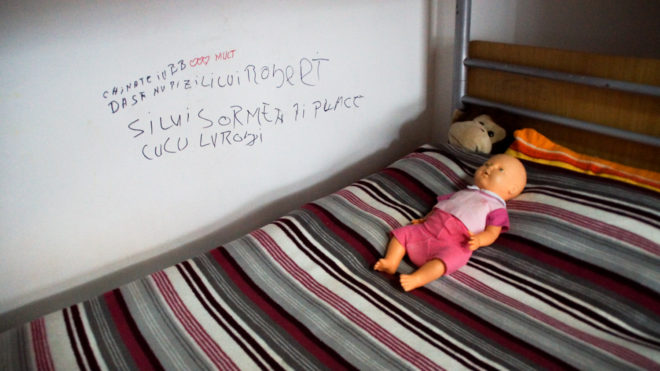

With resolute steps, a small woman gives a tour through a small, stuffy building where it vaguely smells of dampness and sweaty boys. The bedrooms are cosy cluttered with framed pictures on the walls; the hallways are narrow and full of bulging wardrobes. 26 children between 13 and 17 live here, they are sitting in front of the television, doing their homework, or both at the same time. The aim is to make this into a small residential facility as well, the director, who prefers to remain anonymous, tells us. When she took office two years ago, there were 32 children, and a few years earlier 45. Looking at all the bunk beds in the bedroom, you are left wondering where those extra beds would have stood.

“It is better not to talk about it”

In a year or maybe two, this location is going to close, the director says. The children and counsellors will be living in an apartment, but where exactly is still unclear. “We try to prepare the children for an independent life. We teach them to clean up, wash their own underwear. We teach them discipline. Two years ago, nobody thought about that at all: the counsellors did everything.” In the two years that she has been working there, seven employees have resigned. “It might also have something to do with me personally,” she says cautiously. “I do not tolerate anyone who shouts at the children or hits them.” Did that happen? She hesitates, looks away. “In two cases, yes. It is better not to talk about it.”

Against forgetting

Daniel Rucareanu calls for a large-scale investigation and an apology. “Because how on earth can we improve the childcare system if we are not prepared to investigate what went wrong in the past?” Emphasising each word: “We have to clean up the garbage first.”

“The children in orphanages were children of nobody. You could do whatever you wanted with them.” When some boys in his home died, no one cried. “Neither did I. I was just scared. Because if it could happen to them, it could happen to me too. And I knew: if I die, no one will cry either. Nobody remembers that you were ever there. But I have not forgotten them.”