In the summer of 2015, Otakar van Gemund (46) received a call from an unknown woman: ‘Hi Otakar van Gemund. I’m from an international company. Look at your display. Do you see where I’m from? I’m calling from Saint Petersburg. Bye now.’ “I already knew I was being tapped, and this phone call only confirmed that,” Van Gemund says. He is sitting at the kitchen table in his home in a suburb of Prague. His mother is Czech, his father Dutch. After his graduation in the summer of 1989, a few months before the Velvet Revolution, he went to Prague to learn the language.

Defend freedom bare-chested

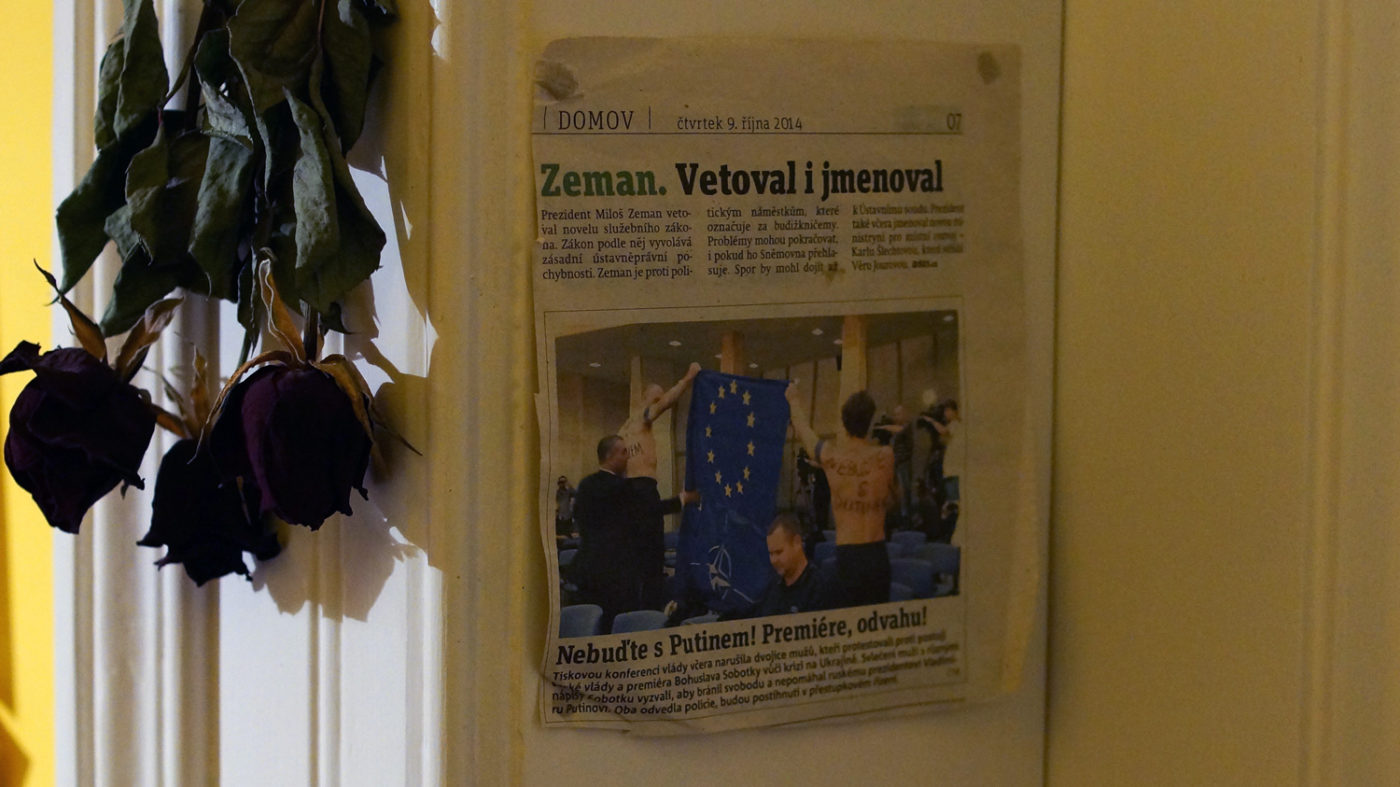

One wall in the kitchen is covered with family photos from top to bottom: Van Gemund with his wife and his two small children, his children in the snow, Van Gemund with his eldest son. Just around the corner hangs an inconspicuous newspaper clipping. If you look carefully, you can discern a bare-chested Van Gemund. With black letters ‘Defend freedom’ and ‘Take courage Prime Minister’ is written in Czech on his chest. It was the first time his activist group Omen (named after the female action group Femen) struck, he says proudly. It happened in 2014, shortly after the annexation of the Crimea. At a normal press conference of the Czech Prime Minister, which was broadcasted live, Van Gemund and a fellow campaigner showed their chests. All newscasts reported on it. Since then, Van Gemund has bared his body on numerous occasions. With his bald head and his stark white torso he is a striking appearance. “By now, I am an ‘old firm’, as the Czechs say. People recognise my face. It makes me good media fodder. And I never give up: the harder it gets, the more interesting it becomes.”

Until the annexation of the Crimea in 2014, Otakar van Gemund had been carrying out occasional one-time ‘hobby-actions’. He was living a quiet life. He earned his money with translation jobs and sometimes worked as an interpreter or ‘stringer’ for the Dutch media. The annexation changed all that. “The occupation was in the news for a few weeks. After that, it all became quiet again. Here in the Czech Republic, people were even complaining about the sanctions against Russia, saying that it would harm the economy. I thought that was very frightening: a foreign power occupies a piece of land and hardly anyone is talking about it. How is that possible?” Van Gemund’s first step was to hang the flags of the Ukraine and the European Union above his door. He hoped his neighbours would follow this gesture, but nothing happened on his street. On Facebook, he searched for allies. In addition to Omen, he set up the activist group Kaputin. With this group – with varying members – he went to airports among and other places, to symbolically wait for people who were put in prison in Russia by Putin’s government or who have inexplicably disappeared.

Putin Taken from behind

Almost three years later, every Czech who watches the news knows his face. Van Gemund thinks that the divide between Eastern and Western Europe is increasing, which is making him very worried. Russia’s growing influence in Europe, and especially in the Czech Republic, has a strong presence, Van Gemund, who grew up in the Netherlands, feels. He sees it happening, but nobody does a thing: “The actions I organise are very time-consuming, but I must to do them; nobody else will. Europe is falling apart in front of my eyes.” He is quite negative about the Dutch attitude – for example when it comes to the Association Agreement: “The Dutch have never been as selfish as they are now. Even when a plane full of Dutch people is brought down, they are willing to do the Russians a ‘favour’ and vote against the association agreement with Ukraine. They don’t give a damn.”

When Van Gemund talks about Miloš Zeman, the first Czech president who was directly chosen by the people, the look in his eyes becomes even more fanatical. Zeman’s campaign was co-financed by the Russian oil company Lukoil – though Zeman himself says that it was a personal donation from one of the employees of the Russian company. Zeman’s populist stance and the ‘cowardly attitude’ of the Czech people bother Van Gemund. “There is hardly any protest. The government is afraid to take a stance against Zeman because he was chosen directly by the people.”

Many of Van Gemund’s actions are aimed against Zeman. Another one is planned in two days. A lot still needs to be done, and therefore he is extremely nervous. “We are going to give the Russians back their little green men.” He gets up, walks to his office, and comes back with several pictures of the heads of Zeman and Putin. They have been made bright green. “We stick these heads on sex dolls,” Van Gemund says, laughing. The little green men symbolise the Russian soldiers who, dressed in green, occupied the Crimea. “Suddenly, they were standing there, like some sort of Martians.” In a few days, together with his fellow activists, he wants to throw the green inflatable dolls over the fence of the Russian embassy in Prague. The pièce de résistance is going to be two male sex dolls of Zeman and Putin, whereby Zeman is taken from behind by Putin. After that, the activists are going to chain themselves to the fence and bare their chests.

'Now you can clean the floor with me'

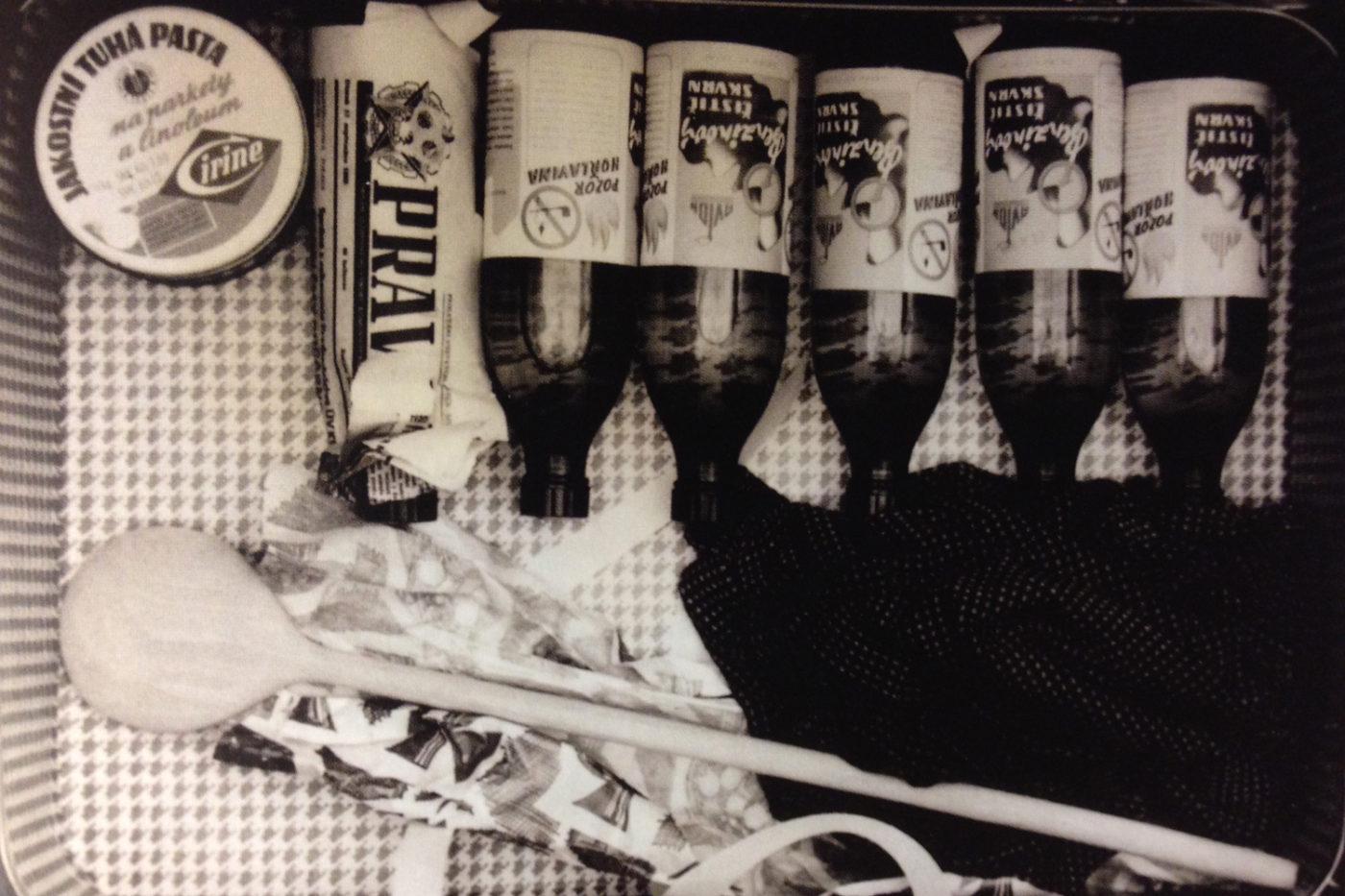

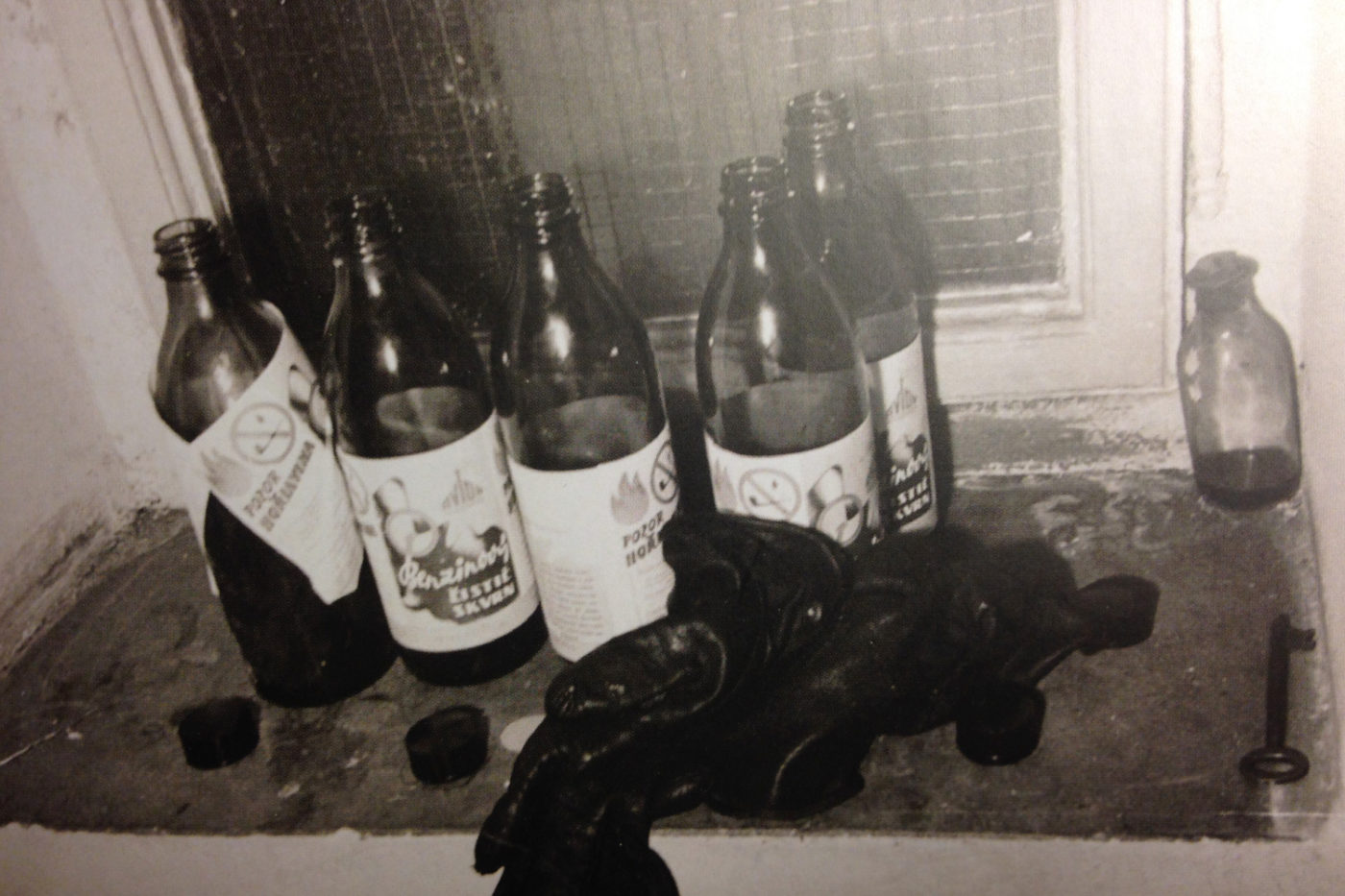

47 years earlier, on 25 February 1969, the student Jan Zajíc walks across the Wenceslas Square in Prague, carrying a grey suitcase. The case contains a large spoon, his shirt, and a dozen half-litre bottles of detergent – bottles with a sticker with a picture of a flame. He walks in a cloud of a pungent chemical odour. Zajíc is remarkably calm.

Less than an hour ago, he asked his friend at the station in Prague to rub his back with parquet cleaner. His friend refused, so he had to do it himself. It took him fifteen minutes, there, in the bathroom of the station. When he was finally done, he tried joking about it with two girls from his school who were with him. “So, now you can clean the floor with me.” Shortly before that, one of the girls had tearfully begged him not to carry out his plans.

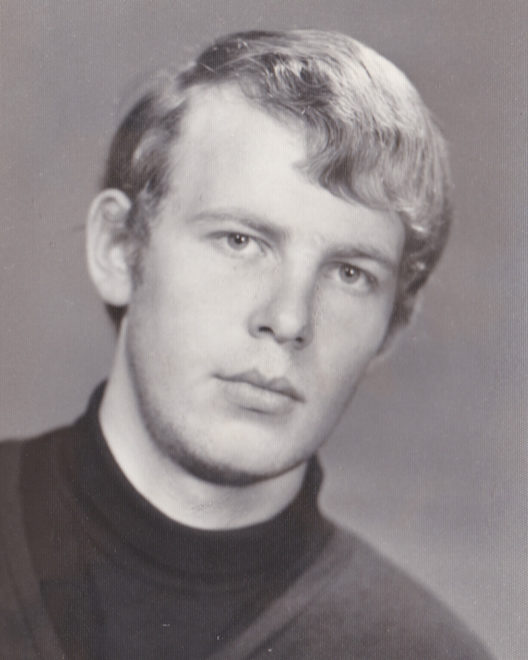

He left his friends behind at the great Wenceslas Square. He wants to be alone now. Jan Zajíc – eighteen years old, 179 centimetres tall, thin, chestnut cropped hair, blue jumper, brown checkered trousers, three-quarter coat, scarf and boots – will change history. This will be the greatest and most important thing he is ever going to do in his life.

He had preferred to do it at the National Museum – a symbolic place at the top of the huge Wenceslas Square where the effect would have been the greatest – but it is closed. The square is crowded, full of shoppers and traffic. At number 39, however, near a shop for household items, there is a tunnel-like passageway that leads into a quiet courtyard. Here he can prepare himself.

Burning body

At approximately fifteen to two in the afternoon, an employee of the shop for household items finds an empty suitcase in the bathroom and a letter sticking half out of an envelope. It smells funny as if someone spilt petrol. She starts reading the letter when she hears screaming. Running into the courtyard, she sees smoke coming from one of the doorways in the tunnel. Behind the doorway is a staircase, at the bottom of the stairs lies Zajíc’s burning body, beside him lies a ladle.

In Prague’s city centre, in this symbolic square, Jan Zajíc was going to carry out the ultimate act of resistance. With the burning ladle as a torch in his hand, he wanted, soaked and smeared with combustibles, to walk into the Wenceslas Square to set himself on fire. An act that would make the whole country think, Zajíc hoped.

Perhaps there was a draft in the tunnel, maybe he was being clumsy, but Jan Zajíc, his body burning, collapsed before he could even reach the square. “I’m not doing it because I want people to cry for me, or because I want to be famous, or because I have gone crazy,” he wrote in a letter which he addressed to all the citizens of his country. “I’m doing it to make sure you will resist and you will not be swept away by dictators. (…) Let my torch ignite your hearts and enlighten your minds. Let my torch light the way to a free and happy Czechoslovakia.”

'I may as well Admit it: I Fled"

Van Gemund’s eyes light up when he hears the name Jan Zajíc. Of course he knows Zajíc's story. He would never go that far, but he admires Zajíc for his courage. There is one thing he wants to be certain of: he is not going to be compared to Zajíc in this article, or is he? What he does is much less heroic, so let that be clear.

Van Gemund had not even been born yet when Zajíc carried out his ultimate act of resistance. In the 70s and 80s, Czechoslovakia had one of the toughest communist dictatorships in Eastern Europe – after Romania and East Germany. Even the Soviet Union was less strict than Czechoslovakia towards the end of communism. At that time, Van Gemund was still living in the Netherlands. He did not go to Czechoslovakia until the summer of ‘89. “When East Germany started to disintegrate, I thought: ‘I must go to Czechoslovakia, I want to see what is going to happen there.’” He did this through a student exchange programme that was used by no other Dutch or Czechoslovakian students. His classes were always early in the morning or late in the day: “They tried to prevent us from coming into contact with Czech students. Most of my Czech friends I didn’t get to know until the revolution had started.”

Initially, there was no revolution to speak of. “Those first months, the regime stubbornly managed to stay afloat. Until 17 November 1989: the day when students traditionally organised a march in Prague for Jan Opletal.” This student was shot in 1939 by the Nazis during a student protest against the German occupation. A few weeks later he passed away. “I only knew about the official demonstration. On the way on the tram, I noticed that people had other plans.” The official demonstration was disrupted almost immediately: “People cried: democracy, freedom! It was the beginning of the Velvet Revolution.”

With friends from his language class, he walked in the direction of the Wenceslas Square. “On the way there we were met by a police cordon. We were enclosed on two sides and they started pressing us against each other.” What he did then? “I may as well admit it,” Van Gemund says, embarrassed. “We fled. I was so afraid that I almost wet my pants.” With a small group he went into a restaurant. There he waited. Van Gemund and his friends were standing between the tables with people dining, while a large group of brave students remained outside, sitting in the street. Despite their peaceful way of campaigning, the students were beaten by police with batons. “In the restaurant, we suddenly heard a terrible noise. The police were standing in a small street - the only way out for students - and were hacking away at people.” Afterwards, Van Gemund saw blood, bras and clothes on the street: “The devastation was incredible. Miraculously, no one died.”

He still regrets not having participated in the protest that day. However, from that moment – the Velvet Revolution lasted a little over one month – he was ready. The show of force by the police was criticised. Three days later, the students took to the streets again. Václav Havel founded the Civic Forum. Every day there were more protests, and people dared to do more. Van Gemund remembers: “In that first week, the regime managed to hang on while acting in a harsh manner. For example, the government tried to prevent information from coming out about what was happening in Prague.” Therefore Van Gemund travelled the country to tell – in broken Czech – exactly what was going on in the capital: “I gave lectures in movie theatres filled with students and high school pupils. It was an incredible time. I just knew: ‘History is written here.’ The years that followed with Havel were golden years. People believed that Europe could be one.”

In early '68 everything changes

Jan Zajíc grew up in the 50s and 60s in Czechoslovakia with the idea that everyone had two ‘faces’: one at home behind closed doors, and one for public life. At home in the village of Vítkov, Radio Free Europe or Voice of America was on often. Those stations were banned, but if you did not mind the interference, listening to them on shortwave was tolerable. With his parents and his older brother Jaroslav, Jan discussed what they heard on the radio. But from a very early age he had learned: nothing of what you hear at home you may repeat outside. It could damage your future, his mother always said.

But in early 1968 everything changes. In the Czech Communist Party, the reformist Alexander Dubček comes to power. He chooses a new direction under the heading of ‘socialism with a human face’. Some Czechs are allowed to travel abroad, new political and social organisations are condoned, and most importantly: the reins of censorship are loosened. Zajíc is astonished. He can go to foreign plays, he can see films in the cinema that were previously banned, and it seems like every week new newspapers and magazines are set up.

But of all things, Zajíc is happiest with the debate meetings: there are discussions everywhere. Zajíc participates in every debate he can find at the school in Šumperk where he studies and boards during the week. He writes poems and pamphlets, and talks with his friends about big issues like democracy. They all believe it: they, the young generation, are going to bring about change. Zajíc feels that everything is brighter, as if the Prague Spring has woken everyone up.

Torch Number one

The happiness only lasts a few months. On the night of 20-21 August, the tanks of the Warsaw Pact drive into Prague and destroying everything. The next morning, Zajíc’s father calls his two sons. “Here, take some money, and flee the country while you still can.” But Zajíc refuses. He has seen the strength of the reform movement – it will not be fazed, will it? So Zajíc continues. He chalks slogans on buildings in Vítkov. And after the summer holidays, he tries to make plans for new actions against the oppressor, with his classmates in Šumperk. At first, the teachers also support the student activism but as the Soviet Union tightens the grip on the country, they back out. He is filled with horror, seeing how more and more people – first the teachers, later the students too – seem to resign themselves to the situation.

Then again something happens that turns Zajíc’s world upside down: on 16 January 1969, the 20-year-old student, Jan Palach, sets himself on fire in the Wenceslas Square in Prague. With this action, he protests against the Russian oppression, and he calls himself ‘torch number one’. In a letter, he demands the lifting of censorship amongst other things. If his demands are not met, others will follow his example, Palach warns. On 19 January he dies from his injuries in the hospital.

Palach’s act seems to wake up the Czech people again. His death inspires tens of thousands of people to take to the streets in a memorial march organised by students. Just like in the summer of '68, the Wenceslas Square becomes the meeting place for everyone who longs for change. There are protest rallies, flyers are being distributed, and poets and artists create lots of work inspired by Palach. Students organise a hunger strike to reinforce Palach’s demands. As soon as Zajíc hears about it, he takes the train from Šumperk to Prague on his own. He does not know the students, but feels a strong urge to join them – he wants to do something.

For days, he sits and talks with them in the square, while all of them are trying to warm themselves on a small coal stove. At night they sleep in tents. Passersby look at their banners and praise their actions. Temperatures are below zero, but the students are boiling inside and have fire in their eyes. Zajíc is sure of it: the power of the people is back. Together they will fight for a free country.

Back in Vítkov, Zajíc tells his parents about the banners, the candles and the mass marches. Now we have to persevere, by force if need be, he explains to his parents and his older brother. At school in Šumperk, he tries to convince his classmates, but Zajíc feels that their resignation is even greater than before. People are afraid of the secret service; they stopped discussing and debating things. They withdrew into their shells. Sometimes he just says it during class, without batting an eye: if nothing happens, maybe I should follow Palach’s example. His classmates do not know if they should take him seriously or if they should laugh at his dark humour.

A new spar is Needed, Torch Number two

The days in Prague have changed him. He was crying during Palach’s burial, standing among tens of thousands of strangers who also wept. That had to mean something, hadn’t it? Zajíc is certain of it: the only thing needed is a new spark. He is that spark, torch number two.

In the farewell letter to his family, he asks for a funeral in Prague: “It will be a manifestation for the world.” But it does not get that far. Under intense pressure from the authorities, the funeral takes place in Vítkov. Zajíc’s death does not cause nearly as big a turnout as Palach’s did. Newspapers pay little attention to it – the few journalists who do write about it lose their jobs because of it. “There is so much I want for you. That is why I have to sacrifice a lot too,” Zajíc had written to his family. But his actions are working against them in many ways. His mother is fired on the spot; his younger sister is not allowed to start university. People stop greeting the Zajíc’s in the street. The flowers on Zajíc’s grave are stolen again and again. Czechoslovakia embarks on a gloomy period of ‘normalisation’. It would take until 1989 for the Wenceslas Square to become the epicentre again of a mass asking for change.

‘Nobody does anything’

The excitement Van Gemund felt in 1989 during the revolution has been replaced by fear and anger. “The fact that many Eastern Europeans are now so fiercely against the arrival of refugees is largely due to their history with communism,” Van Gemund thinks. “People who grew up in communism never learned to think critically. They are used to propaganda.” He is quiet for a moment. Then he says: “The Czech people were crushed by the millstone of communism. Politicians have taken absolutely no responsibility for their actions – just like in many other former communist countries. Those politicians are huge hypocrites: with one hand they beg for money from the EU, with the other they warn the people for the same EU.”

In two days he is going to chain himself to the fence of the Russian embassy in Prague – if everything goes according to plan. The chaining will happen after he has pushed the sex doll with the face of Putin over the fence. The goal is for the helium filled doll to jump across the lawn like a dancer. Drawing attention to the issues with controversial actions is the only thing he can do, Van Gemund says. If necessary he will show the Czech people what activism is every day for the rest of his life: “I want to show them that what I do can actually be done. It is part of having a democracy.” He sighs: “I’m just a moralist too, someone who points his finger. I certainly do it for my own peace of mind. If it all ends badly, at least I have tried to do something.”