«Необходимо уметь свободно мыслить без давления»

ДВА ПОКОЛЕНИЯ, ОДНА ИСТОРИЯ

В 1968 году Андрей Сахаров написал свое новаторское эссе против ядерного оружия и гонки вооружений времён Холодной Войны. Советская власть не отблагодарила за это уважаемого русского физика-ядерщика и отправила его позднее в ссылку на квартиру в Горьком. В подъезде того же дома проживает на тот момент и юная Любовь Потапова. Тогда она не решается заговорить со знаменитым диссидентом. В настоящее время она является директором музея-квартиры Сахарова. Посетителей музея теперь раз два и обчелся, в то время как эссе Сахарова остается актуальным и через 50 лет после публикации. «Ни один из мировых лидеров не обладает его качествами»,- считает Потапова.

Автор: Флорис Аккерман Переводчик: Яна Смирнова

Нижний Новгород, 2018 г.

ВСЁ ЕЩЁ АКТУАЛЬНО

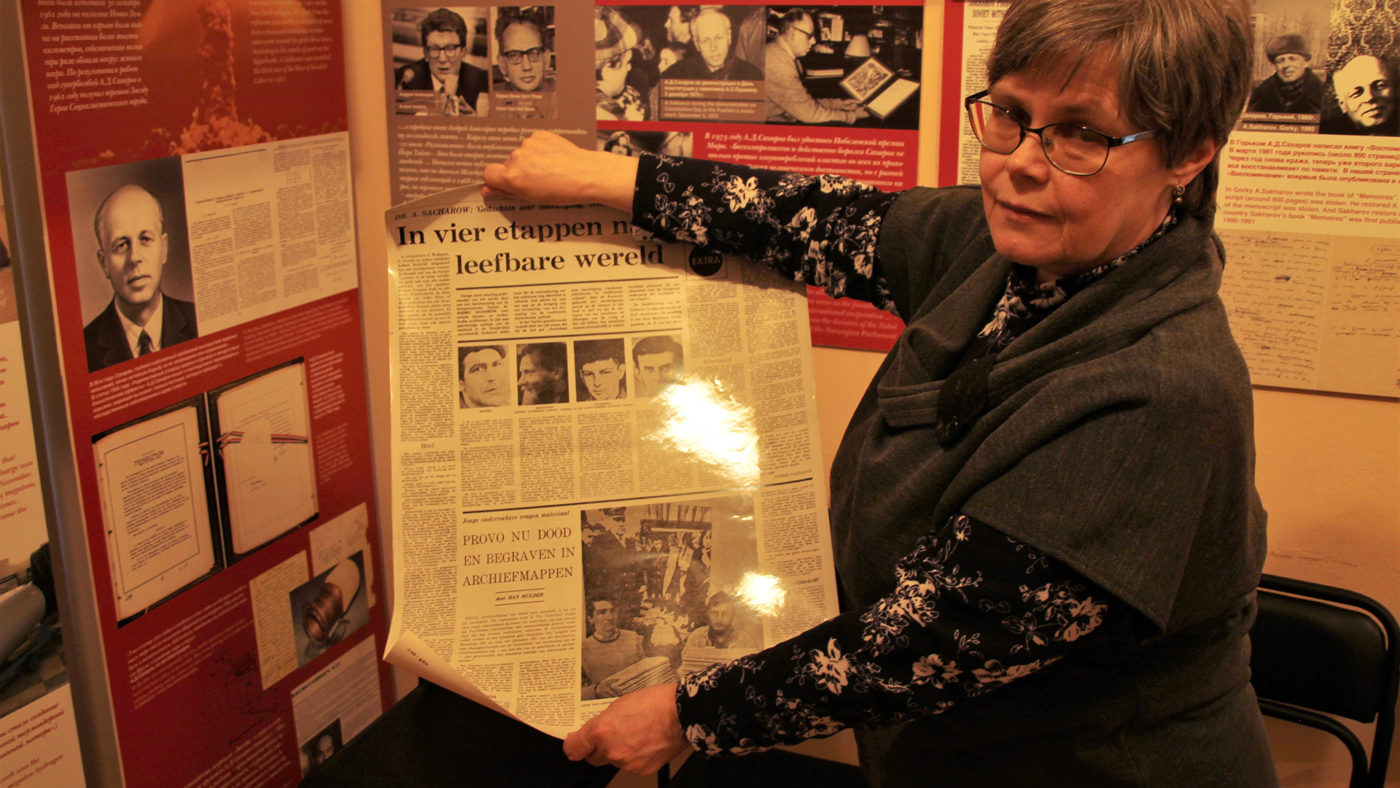

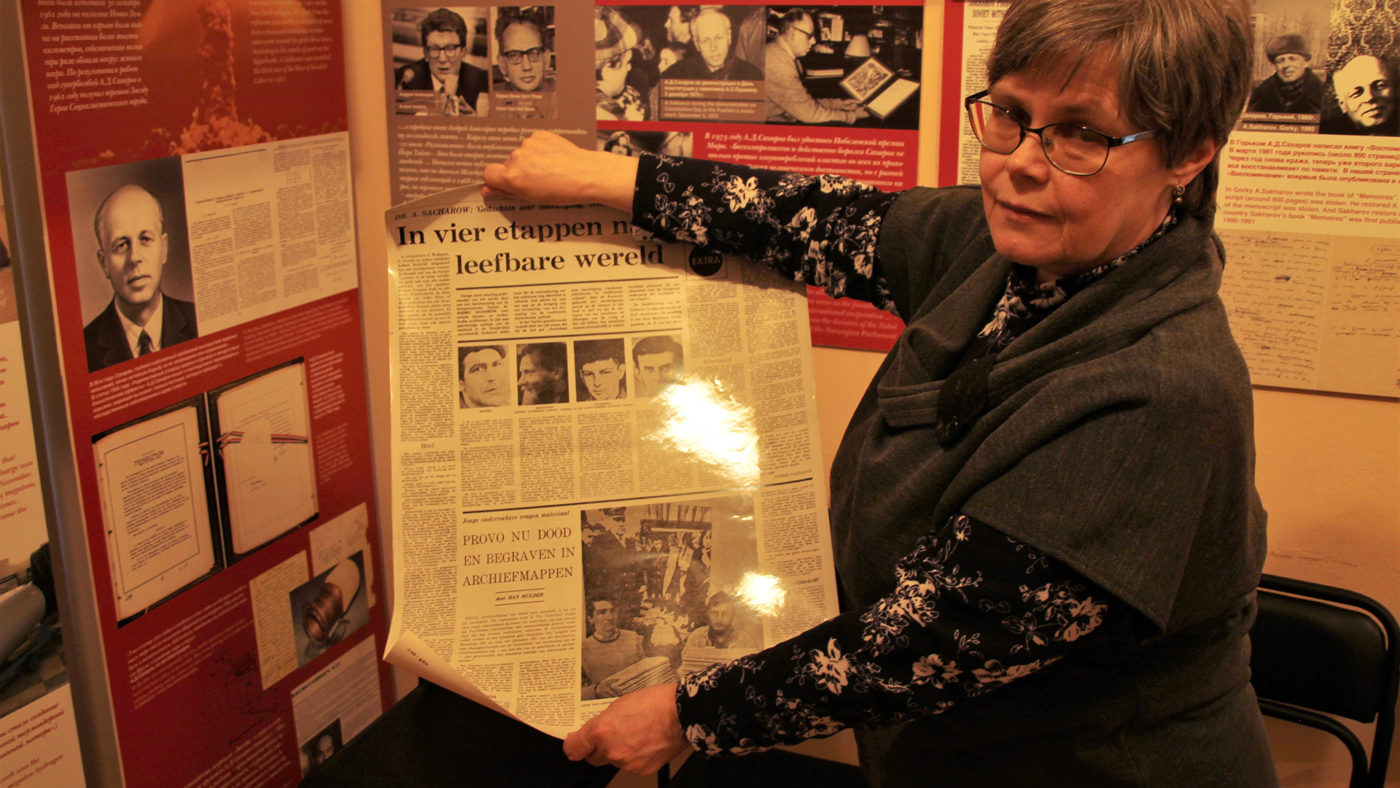

«Его статья всё ещё актуальна», – говорит Любовь Потапова. Она уходит и возвращается с ламинированной страницей голландской газеты «Het Parool» от 13 июля 1968 года. Она разворачивает ее на столе в квартире-музее Сахарова в Нижнем Новгороде, за четыреста километров к востоку от Москвы. Сразу бросается в глаза заголовок “К пригодному для жизни миру за 4 этапа”. Это вторая и последняя часть знаменитого эссе Андрея Сахарова, отца советской водородной бомбы. Первая его часть была опубликована неделей ранее в газете «Het Parool».

Директор Потапова ведет экскурсию по музею Сахарова в Нижнем Новгороде спустя полторы недели с момента послания российского президента Владимира Путина в начале марта этого года, в котором он хвалится новыми сверхзвуковыми ядерными ракетами. Музей расположен в четырехкомнатной квартире, куда Сахаров был поселен в 1980 году за свою непрекращающуюся критику cоветской власти.

Потапова,направляя меня по коридору, в конце которого висит портрет Сахарова, указывает на гостиную и спальню c коричневой мебелью с оранжевой обивкой и на семейные фотографии в шкафу, расставленные как в былые времена. Она замолкает в выставочном зале, посвященном истории жизни Сахарова, которая показана на основе газетных статей, документов, фотографий и рассказов из биографии Сахарова. Это не музей с сенсорными экранами и планшетами.

Кто сейчас читает его эссе “Размышления о прогрессе, мирном сосуществовании и интеллектуальной свободе”, не может не поразиться паралеллями с настоящим временем. Ученый-ядерщик еще пятьдесят лет тому назад указывал на опасность ядерного оружия. Он порицал военную агрессию, критиковал национализм, экстремизм, диктатуры, догматизм и расизм. Сахаров призывал к интеллектуальной свободе и не только резко критиковал отсутствие демократии в Советском Союзе, но проявления расизма в США. И, что немаловажно, он предлагал решение этих проблем в четыре этапа, среди прочего путем срастания социализма и капитализма как альтернативы полному уничтожению человечества.

В офисной части музея Потапова (56 лет) ставит на стол печенье, шоколад и чай. Она говорит обдуманно и тонко, в духе бывшего жильца этой квартиры. Она не жалеет времени для рассказа о жизни и идеях человека, с которым она никогда не обменялась и словом, но который кардинально повлиял на её жизнь.

Директор Любовь Потапова показывает газету «Het Parool» со статьей Сахарова. Фото: Флорис Аккерман

Объект 1968

ДВА РЯДА КОЛЮЧЕЙ ПРОВОЛОКИ

В 1968 году Андрей Сахаров работает на Объекте – удаленном ядерном исследовательском центре среди полей и лесов, окруженном двумя рядами колючей проволоки. 10 июля 1968 года, после выхода своего эссе, он слушает радио. В своей автобиографии он пишет об этом так:

«10 июля […] я начал слушать вечерний выпуск BBC (или «Голоса Америки», уже и не помню) и услышал упоминание своего имени. Сообщили, что 6 июля голландская газета напечатала статью члена-корреспондента Академии Наук СССР А.Д. Сахарова […].»

Своё эссе Сахаров написал после осознания того, что для него, как представителя интеллигенции, наступил момент открыто высказаться по важным вопросам своего времени. Как отец советской водородной бомбы он чувствовал свою личную ответственность. Благодаря своей работе он знал тоталитарную советскую систему и видел опасность руководства, которое может действовать при отсутствии оппозиции. Ранее в том же году он услышал о «Пражской весне». Он чувствовал волнение, надежду и энтузиазм в отношении идей «социализма с человеческим лицом». В Советском Союзе в том году тоже произошло что-то примечательное. Сахаров назвал это своего рода мини-выпуском «Пражской весны». После того как были осуждены три диссидента в их защиту была собрана тысяча подписей. Беспрецедентно в период тогдашнего удушающего режима.

Эссе Сахарова явилось для Кремля шоком. Москве не были нужны опасные идеи советского ученого c высоким статусом, который видел сходство между Сталиным, победителем во Второй мировой войне, и Гитлером, и который не отвергал идеологического врага – капитализм. Два смертных греха. Власти запретили публикацию. Эссе закончило свои дни в самиздате (подпольных литературных изданиях) и распространилось в небольшой аудитории. Народ так ничего о нем и не узнал.

Но статья действительно нашла свой путь за границей и очутилась у голландского писателя Карела ван Хет Реве, который в то время был корреспондентом в Москве. Сахаров в своей автобиографии описывает это так: «[…] Я не знал, что несколько человек уже пытались передать рукопись за границу через корреспондента американской газеты «New York Times», но тот отказался от рукописи, так как боялся, что это будет фальсификацией или провокацией. После этого она была передана корреспонденту голландской газеты Карелу ван Хет Реве в середине июня Андреем Амальриком (диссидентом и писателем, ФА), кажется, в «Amsterdams Avondblad» (имеется в виду «Het Parool», ФА)».

Несмотря на отсутствие личного знакомства, Ван Хет Реве принес Сахарову всемирную славу. За границей внезапно слышат другой голос из закрытого советского блока. И не просто от кого-либо, а от отца советской водородной бомбы, с которым в Советском Союзе всегда обращались с большим уважением. После публикации в «The Parool» последовала публикация в «New York Times», а затем эту эстафету подхватил весь мир. «Я припоминаю, что, по данным Международной ассоциации издателей, общий объем моей статьи в 1968-1969 годах составлял восемнадцать миллионов. Я был на третьем месте после Мао Цзэдуна и Ленина и обгонял Жоржа Сименона и Агату Кристи», – не без гордости пишет Сахаров.

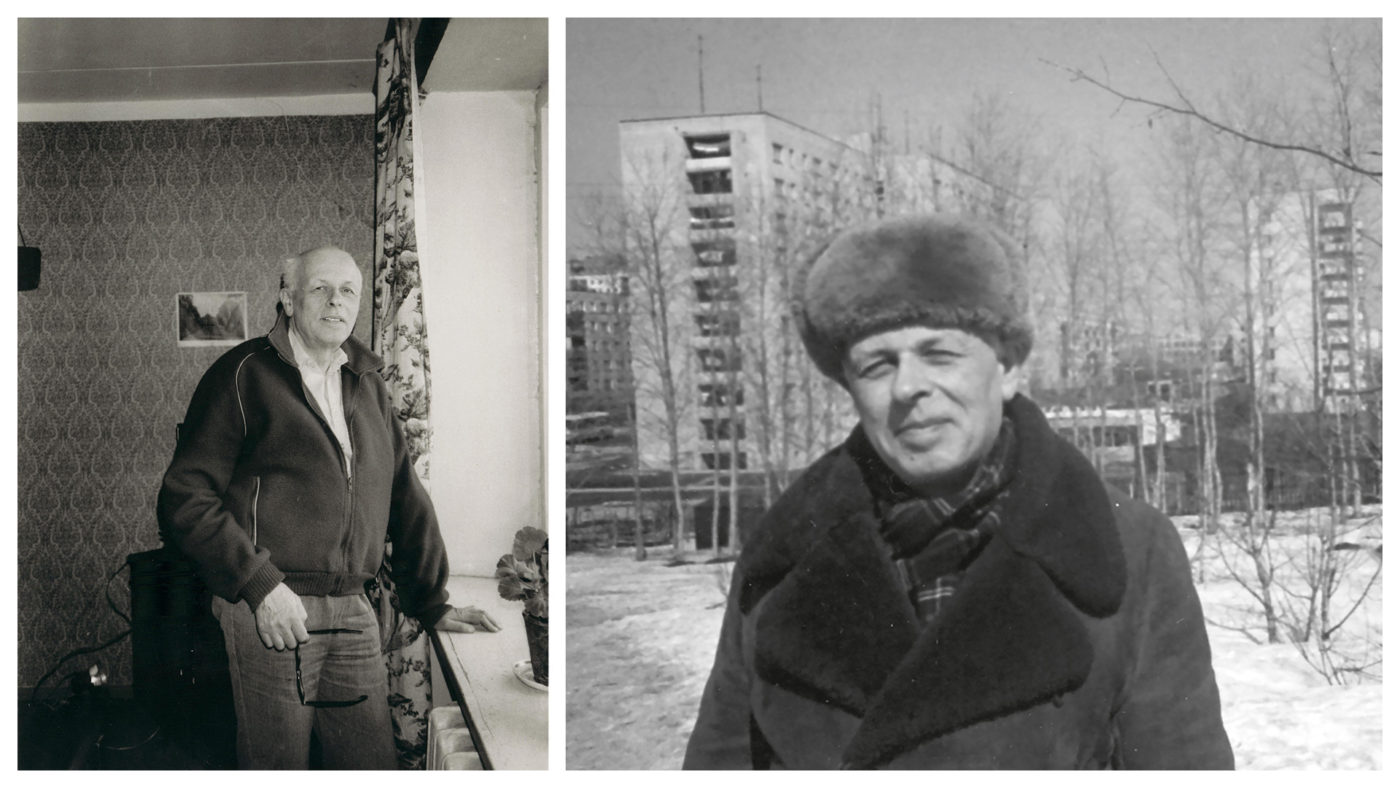

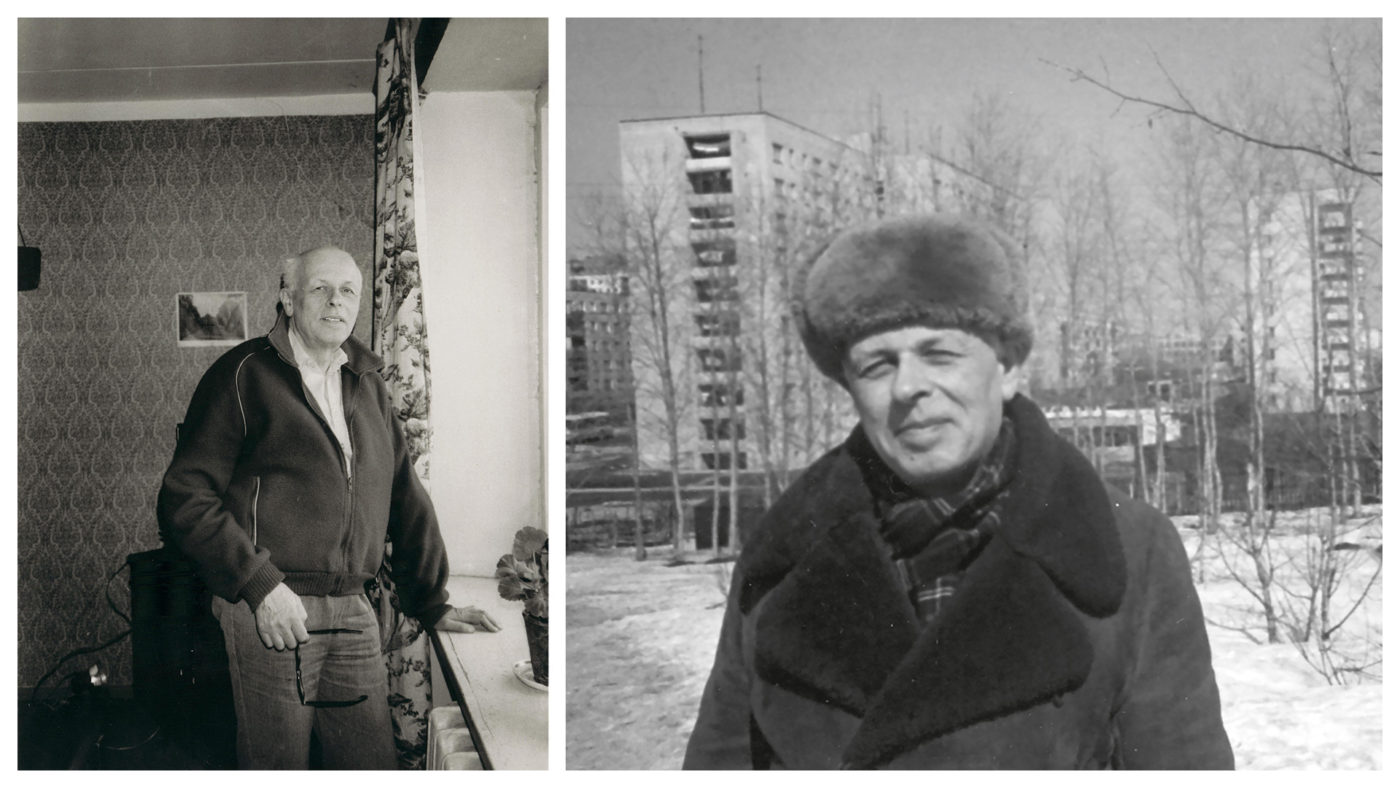

Андрей Сахаров

Горький, 1980 г.

МИЛИЦИОНЕР ОХРАНЯЕТ ВХОДНУЮ ДВЕРЬ

«Статья полностью изменила жизнь Сахарова», – рассказывает Потапова. Из ученого он превратился в гуманитарную, просвещенную совесть страны. Диссиденты в Советском Союзе обрели свой рупор. В 1975 году Сахаров получил Нобелевскую премию мира. Ему не разрешили покинуть страну для получения этой премии.

В 1979 году Сахаров в иностранных СМИ критикует Советский Союз за вторжение в Афганистан. Его заявления снова вызвали гнев советских лидеров, а Кремль в январе 1980 года отправляет его с женой на самолете в Горький. С билетом в один конец он отправляется в изгнание. Сахаров оказался в четырехкомнатной квартире в спальном районе города. Горький (названный в честь русского писателя Максима Горького и в 1991 году переименованный в Нижний Новгород) закрыт для иностранцев из-за наличия военной промышленности. Кремль не заинтересован в подглядывании, поэтому ни один журналист не имеет разрешения навещать Сахарова. У него нет телефона. Входную дверь охранял милиционер, а КГБ держала вахту на улице. Когда Сахаров покидал свою квартиру, он всегда находился под наблюдением агентов КГБ. За его машиной всегда следовали, часто даже на двух машинах, пытаясь его запугать. «Иногда они пытались напугать нас, создавая ситуацию, которая может закончиться катастрофой», – напишет Сахаров позже в своей автобиографии.

В подъезде дома, где жил Сахаров, подростком жила и Любовь Потапова. Она рассказывает, как за несколько дней до приезда Сахарова у многоквартирного дома появились милицейские машины. Жильцы заподозрили, что должно произойти что-то особенное. После приезда новых жильцов все поняли, кто поселился в квартире на первом этаже. «Мы знали его в лицо. Андрей Дмитриевич был, конечно, известным физиком. Но мы не знали, почему он поселился в нашем доме.»

«От других людей, слушающих иностранные радиостанции, я услышала, почему Сахаров остался в Горьком, – продолжает директор музея Сахарова. «Но меня это не занимало. Мне было восемнадцать лет. Я училась на первом курсе и заводила новых друзей ». Она иногда встречала его у входа в квартиру, но они не обменивались ни словом. «Он понимал, что не должен с нами разговаривать. Иначе он подставил бы нас под удар. И мы знали, что нам самим тоже лучше не заговаривать с ним. Мы ничего не знали о его взглядах. Об этом мало что говорили. Вместе с другими студентами мы однажды спросили нашего преподавателя политэкономии, почему Сахаров находился в изгнании. Его ответ был: «Я не знаю и вам советую не знать».

Квартира, в которой Сахаров был заперт в Горьком, в настоящее время Нижнем Новгороде. Фотография: Флорис Аккерман

Горький, 1980 г.

«ЗДРАВСТВУЙТЕ, С ВАМИ ГОВОРИТ ГОРБАЧЁВ»

Вечером 15 декабря 1986 года в дверь Сахарова позвонили. Двое рабочих в сопровождении офицера КГБ начали устанавливать белый телефон. «Завтра около десяти Вам позвонят», – сообщил при прощании кагэбэшник. На следующий день в три часа дня, когда Сахаров собирался за хлебом, телефон зазвонил.

«Здравствуйте, с Вами говорит Горбачёв».

«Добрый день», – сказал Сахаров.

«Вы получите возможность вернуться в Москву, – сказал Горбачев, – указ Президиума Верховного Совета будет отменен».

Два дня спустя Сахаров и его жена сели на поезд в столицу. Освобождение Сахарова вписывалось в картину наступления послаблений в Советском Союзе под руководством Михаила Горбачёва. В Москве Сахаров стал прилагать всяческие усилия по сокращению количества ракет в Европе. Он призывал к сокращению Советской армии и указывал на опасность ядерной энергии. В марте 1989 года он был избран депутатом Верховного Совета, но скончался 14 декабря того же года. Большое количество народа пришло отдать ему последнюю дань. Два года спустя в его бывшей квартире в Нижнем Новгороде открылся музей Сахарова.

Музей-квартира Сахарова с подлинным белым телефоном на столе, по которому Сахаров говорил с Горбачевым. Фотография: Флорис Аккерман

Нижний Новгород, 2018 г.

«ЧТО ВАЖНЕЕ?»

«Годы после падения Советского Союза в 1991 году стали трудным временем», – вспоминает нынешний директор музея. «Я преподавала математику в школе, но зарплату мне не платили». С 1991 года Нижний Новгород больше не закрытый для иностранцев город. «Россия открылась. Стали писать обо всём. На книжном рынке появились всевозможные книги и журналы. Я все больше и больше узнавала историю Сахарова. Затем, в 1993 году я увидела вакансию в кассу музея и пришла сюда на работу. После этого я работала здесь гидом, исследовательским ассистентом, главным куратором, а с 2000 года – директором. В первые годы сюда приходило много посетителей. Даже его бывшие охранники приходили посмотреть, как жил Сахаров».

Экскурсионные автобусы музей Сахарова больше не ездят. В год он имеет только две тысячи посетителей. В школах детям ничего не рассказывают о нем. Память о Сахарове постепеннно стирается. «Россияне старше сорока лет, воспитанные в Советском Союзе, восхищаются его научной деятельностью, но считают его плохим политиком», – говорит Потапова. «Но его эссе по-прежнему имеет значение в свете нынешних отношений между Россией и Западом. Несмотря на то, что между тем и настоящим временем существуют различия», – подчеркивает она. «Существующие мировые лидеры могли бы многому научиться из решений Сахарова», – говорит Потапова, потому что он перешагнул национальные интересы и отстаивал прежде всего интересы человека. Потому что: «Что важнее? Человечество или ваша собственная страна? »- спрашивает она риторически. «Этот вопрос более уместен, чем когда-либо. К сожалению, политики не думают в духе Сахарова».

Ученый-ядерщик пятьдесят лет назад подчеркивал важность военного равновесия. Ни одна страна не должна превосходить другую. Иначе соблазн нападения станет слишком велик. Именно на эту тему Путин регулярно выражает недовольство в отношениях с Западом. Сахаров также придавал большое значение интеллектуальной свободе, которая позволяет народу контролировать и оценивать действия властьимущих и выдавать новые свежие идеи.

«Необходимо уметь свободно мыслить без давления», – подчеркивает Потапова. «Когда люди открыто говорят о проблемах, это приводит к их решениям. Тогда нет необходимости применять оружие. В России больше свободы личности, чем во времена Советского Союза, но полной свободы здесь нет. Посмотрите на убийство Бориса Немцова (политик и критик Путина, убитый в 2015 году, бывший губернатор Нижегородской области в 1990-х годах, ФА) ». Затем подавленно добавляет:«До сих пор неясно, кто был заказчиком. Политики высшего звена должны были бы следить за ходом расследования, а не молчать. Сахарову бы это всё не понравилось».

Потапова не видит нового Сахарова. «Никто не обладает таким мышлением. Он сразу мог видеть суть проблемы, там, где нам нужно сделать десять шагов. В России нет никого с таким видением. Ни один мировой лидер не обладает им. А нам нужен такой человек».

В музее, финансируемом местными властями, все сосредоточено на сохранении и распространении наследия Сахарова и его идей. Жемчужина музея – белый телефон в гостиной – подлинник, который вызволил Сахарова из ссылки. Потапова чувствует свою связь с ученым-физиком. «Конечно, мне было бы очень интересно поговорить с Сахаровым. Но тогда это было невозможно. Вся эта система наблюдения, охранник у входа, который никого не пускал … Было ясно, что с ним нельзя разговаривать. Можно сожалеть, если ничего не сделал, хотя мог бы сделать. Но в той ситуации я не могла говорить с Сахаровым, поэтому я не могу сожалеть об этом».

Помимо интервью с Любовью Потаповой, эта статья основана на интервью с Мариной Шайхутдиновой, главным куратором музея Сахарова в Нижнем Новгороде и Сергеем Лукашевским, директором Сахаровского центра в Москве. Кроме того, я разговаривал с Дмитрием Сусловым, доцентом факультета экономики и международных отношений в Высшей школе экономики в Москве и программным директором дискуссионного клуба и аналитического центра Валдай. Материалы также взяты из автобиографии Андрея Сахарова: «Воспоминания».

STRATEGY 6: Keep the truth to yourself

STRATEGY 6: Keep the truth to yourself