‘You’re Polish, right? Could you paint my house?’

‘You’re Polish, right? Could you paint my house?’ 29 December 2015

KRIS FLOREK (34) from Poland came to the Netherlands in 2002 and is an entrepreneur.

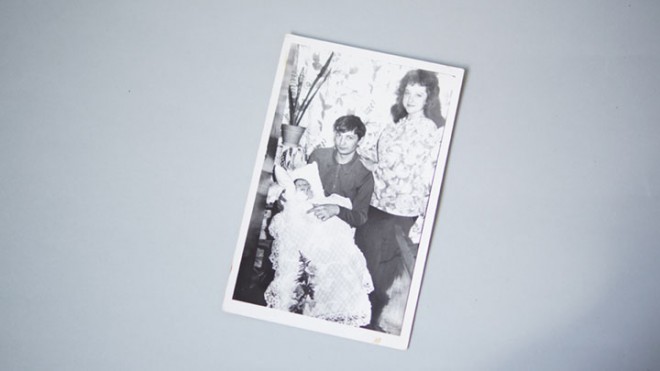

KRIS FLOREK (34) from Poland came to the Netherlands in 2002 and is an entrepreneur.“My parents are still young in this picture, around eighteen years old I think. They look like anything is possible still. That’s how I want to remember my parents.

My parents’ lives revolve around alcohol, mostly. When I was young, I made the boy scouts my second home. My parents lived in a different world and it was hard to communicate. I often found them in the kitchen, vodka bottle on the table. I learnt to cope with having no food.

I was a student until I was 22. I couldn’t afford it any more. My older sister had already moved to the Netherlands and said: ‘Kris, if you come over for the summer break you can earn some extra cash here’.

I slept on the floor in my sister’s sunroom. I couldn’t find a job. Poland wasn’t part of the EU yet and I didn’t know any language but Polish. Still, I knew I would stay. I had fallen in love with the Netherlands. The Dutch have a single word for giving or granting someone something out of kindness: gunnen. We don’t have that in Poland.

One day, my sister’s neighbor said: ‘You’re Polish, right? Why don’t you paint my house?’ I thought it was weird, because I couldn’t paint. I watched every single YouTube video that featured painters or was about handymen. I rode my bike past painters in the neighborhood to see how it was done.

My first job wasn’t my best work, but the neighbor was happy. Shortly after that, another neighbor needed help, and another – I ended up painting the entire area. I offered to do carpentry, too, as I had been preparing for that.

The first money I made I invested in tools and a car. It was a rare sight: a Polish guy with a Dutch license plate and quality tools. I always took my shoes off when I entered a customer’s home. They might have found it strange, but at least they trusted I’d do an accurate and clean job.

I started my own home-maintenance company. It expanded rather quickly, and by 2009 I was an LLC. I now have three businesses and I’m starting a fourth in Poland, where I’ll be selling Dutch fries and classic orange ladies’ roadsters.

My parents don’t understand my life. Being sixty-five and having been druk your entire life, you lose your sense of reality. I’ve been taking care of them for years. I pay their rent, electricity, and water bills. I love them to bits. Had they been different people, I wouldn’t have been who I am today. I’m happy.

For a long time, I wanted to show the Dutch that people from Poland can make it, too. That things can be different: it’s me, the Polish guy, who helps Dutch people find a job. Today, I want to show fellow Poles how to succeed. They often think I’m rich because my family must be rich, too. When they hear how I grew up they realize how their lives weren’t so different. If I can do it, so can they.”

MISHA FURMAN (67) left Lithuania in 1969 and came to the Netherlands via Israel. He plays with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and teaches at the Rotterdam Conservatory, among other things.

MISHA FURMAN (67) left Lithuania in 1969 and came to the Netherlands via Israel. He plays with the Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra and teaches at the Rotterdam Conservatory, among other things.

LYNA DEGEN-POLIKAR (49) came to the Netherlands in 1992. She works as a GGD psychologist.

LYNA DEGEN-POLIKAR (49) came to the Netherlands in 1992. She works as a GGD psychologist.

MARIO PANEV (33) came to the Netherlands from Bulgaria for the first time in 1994. After years of traveling back and forth, he settled in Hilversum. Panev has his own construction company.

MARIO PANEV (33) came to the Netherlands from Bulgaria for the first time in 1994. After years of traveling back and forth, he settled in Hilversum. Panev has his own construction company.

EUGENIUSZ BRZEZINSKI (65) left Poland and fled to the Netherlands in 1982. He’s director of operations at GGZ Keizersgracht in Amsterdam.

EUGENIUSZ BRZEZINSKI (65) left Poland and fled to the Netherlands in 1982. He’s director of operations at GGZ Keizersgracht in Amsterdam.

IWONA LISIECKA (28) came to the Netherlands for the first time in 2012, and has been visiting ever since in the hopes of finding a job as a product designer.

IWONA LISIECKA (28) came to the Netherlands for the first time in 2012, and has been visiting ever since in the hopes of finding a job as a product designer.

IOANA TUDOR (34) ) is a performer and theater maker. When she was ten years old, she and her family fled Romania after Ceaușescu was overthrown.

IOANA TUDOR (34) ) is a performer and theater maker. When she was ten years old, she and her family fled Romania after Ceaușescu was overthrown.

ELITSA YORDANOVA (39) came to the Netherlands in 2001. She’s a social worker, head of the Bulgarian school, and runs a construction company with her husband.

ELITSA YORDANOVA (39) came to the Netherlands in 2001. She’s a social worker, head of the Bulgarian school, and runs a construction company with her husband.

ANDREAS VLASZATY (75) fled Hungary in 1956 and came to the Netherlands. He’s a retired psychiatrist.

ANDREAS VLASZATY (75) fled Hungary in 1956 and came to the Netherlands. He’s a retired psychiatrist.