A true story by Blanka K.

This story arrived to us by email, it’s written by Blanka K. and reflects her own personal experience with the dark sides of the former regime, where personal feelings and power politics get messed up. Documentary maker, Brit Jensen, has asked Mrs. K for an interview, but she replied that these are things she is still unable to speak about. This is her letter.

The year 1990 found me standing at the Andel square in Prague together with Standa. We stood facing each other, carefully observing one another. We were both in our forties.

“Come on, let’s have a drink!” Standa said tentatively and took hold of my elbow. I pulled away and looked at him sceptically, not really understanding a thing. Then I slowly turned around and walked away from him in a calm, but firm pace. That’s the point where Standa must have known that he’d just lost me forever. But it all started innocently and so long ago it’s almost hard to remember…

HE STOLE A KISS

The first kiss he stole from me at the stage during an amateur theatre performance of the novel Márinka by Mách. We were both young, and why deny that I must have looked pretty as Márinka. That was the first time Standa realised that his relationship to me, a slightly older friend, was transforming into something deeper.

Years passed and nothing seemed to change between us. We shared common interests, both loving books and theatre, and we regularly met in his parents’ villa, which they with a perfect sense of timing and foresightedness had donated to the state long ago. I turned down Standa’s shy, boyish endavours, but probably he was still carrying that first kiss with him, nourishing hopes.

At that time he was attending librarian school. He was ambitious and became one of the best students. He kept his feelings secret, probably out of fear that I’d tell him there was no hope of us having a relationship. Looking back, I suspect that maybe he was secretly hoping that his success at school would change things between us?

My wedding with Tomas must have shocked him. At the ceremony he wore a wry smile and made hypocritical toasts for us. While congratulating me he stole the second kiss from me right in front of Tomas’ eyes.

(…)

I NEED YOU

We lost sight of each other for a while. Standa finished his studies and changed his work at the library for a job as a shop assistant in a big bookshop. He was happy and everything would probably have stayed this way. But then sudden change came around when he received a postcard from Munich, to where I’d unexpectedly emigrated together with Tomas in the seventies – pressured by the circumstances of the times. The greeting wasn’t anything more than what you write on a holiday, something like ‘It is nice here and we’re doing well’. However, Standa read something in between the lines: I’m unhappy here, I need you…

He decided to go. During the interview to obtain a passport he must have promised to turn in a report upon his return. A stupid formality, he thought like many before him. Why not? There won’t be any return!

Our reunion in Munich was warm and friendly, but I felt how Standa’s teenage dreams awakened again. I kissed him – for the third time – as a welcome, and that was a mistake! Probably he thought that Tomas was too down-to-earth and pragmatic too satisfy my romantic soul and that I’m not very happy in Germany. And true enough, I did suffer from loneliness and homesickness.

Standa’s exit visa was expiring in ten days, but soon he admitted that he was considering staying in Munich. We weren’t trying to persuade him to stay, neither were we discouraging him. Instead, we tried to create a realistic outline of what would be in store for him: Finding work, adapting to the work and pace while proving that socialism hadn’t spoiled him. Getting to understand the local mentality and turn the initial distrustfulness into his advantage. Also, the simple advice to find new friends and good colleagues might turn out being more difficult than it seems at first.

Especially my husband insisted that Standa shouldn’t rush the decision. As the tenth day, the day of departure, was approaching, Tomas took Standa to see our doctor, a compatriot, who issued a certificate of sudden disease.

From the point when Standa decided to stay, Tomas and I started introducing him to all of our friends. We went with him to the authorities, helped with the documents at the immigration police and the asylum application. We found an apartment for him and helped with everything in words and deeds. A couple of months went on like this. Standa spent the time trying to win me over, but I refused and finally he realized that he wouldn’t succeed. He wrote a short letter, bitter and aggrieved, and caught the first train to Prague. He probably knew he would have plenty to explain, but I guess he wasn’t imagining the carousel of endless interrogations and interviews, which started as soon as he was back home.

FINALLY PRAGUE

Years passed and finally in ’89 it began stirring in the Eastern Bloc. Like all other compatriots in the West Tomas and I were excited and we were impatiently waiting for the moment when we could finally return to our home – and hopefully stay forever.

But how was Standa dealing with the changes on the other side of the iron curtain? I wasn’t to find out until upon my return.

(…)

Finally Prague! Sprinkle with a think layer of white snow, unstained by lies and injustice. The free, golden city with the hundred towers. We listened to the melody of the language. We ran around town, unable to get enough of the mosaics, the side-walks, the trams, the houses, the streets…

The reason Tomas had emigrated back then was that somebody has informed against him. Now he wanted to know and decided to take a look in the archives of the Secret Police (StB). What we found in the list of secret StB collaborators, was as much a surprise for Tomas as it was for me. The letters began dancing in front of my eyes: Stanislav Vébr, agent, code name Giant. I know that a lot of people were on the list wrongly, either because they refused collaboration or because they signed under pressure but didn’t actually provide any information. On the other hand, a considerable amount of archive material was shredded. What to do? I wouldn’t believe anything until Standa would tell me himself.

Our meeting was conducted in an atmosphere of mutual mistrust and watch-and-wait-mode. We stood in front of each other on the Andel square in Prague and watched each other disbelievingly.“Why don’t you object, why don’t you clear yourself?” I asked insistently, tears welling up in my eyes.Standa remained silent for a while and smiled uneasily.

“Come on, let’s have a drink!” he finally said with a hollow voice and grabbed my elbow. Was this supposed to be an apology? Or a confession maybe? I turned away from him.

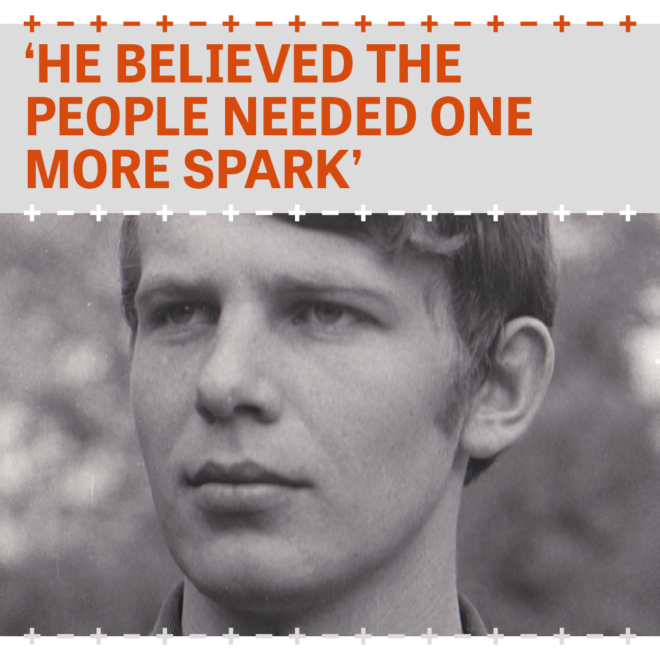

Constantin Jinga was injured when the revolution broke out in Timișoara.

Constantin Jinga was injured when the revolution broke out in Timișoara.

MIRKA CHOJECKI-NUKOWSKA (60) fled Poland in 1987.

MIRKA CHOJECKI-NUKOWSKA (60) fled Poland in 1987.