8 September 2016

“In the Czech Republic it is extremely hard to find anyone who would admit they once were a member of the Communist Party. The country really stands out in this respect. In many former communist states you will see the same phenomenon, but it’s much stronger in the Czech Republic than in other countries,” Eastern Europe expert Carlos Reijnen explains. According to Filip Bloem, historian and expert on the Czech Republic, people do talk about communism, but not when they are amongst friends and family: “Politicians, intellectuals and artists certainly talk about communism. In the public debate the topic is present. But as soon as it gets close and becomes personal, it’s a different story.”

Remaining silent

The Czechs were once strong supporters of communism. In the ‘60s, the Communist Party had 1.5 million members. Moreover, to this day, the country has a Communist Party, which invariably can count on 10 to 15 percent of the vote. Because of their ‘red’ history and the big role the Communist Party still plays, it is difficult to talk about the past for many Czechs.

According to Reijnen, the Czechs, in a sense, had a role in their own oppression: “The Czechs themselves helped the communists to power while the communist ideology was imposed on the people of other countries. There, the Soviet Union would just put a communist regime in place, but in Czechoslovakia the Soviet Union was supported by the public.”

The ongoing existence of the Communist Party makes it harder to talk about communism as well. Reijnen: “Since communism is still so politicized in the Czech Republic, it is actually even more difficult to say that you once were a member. In the Czech Republic communism in not a faded photo from the past, it is still a daily reality.”

The communist tradition

Long before World War II, the Czechs had a Communist Party, which was founded in 1921. Bloem explains: “In the Czech Republic, then still part of Czechoslovakia, the communists met with an exceptional amount of support. They became the second biggest party in the parliamentary elections of 1925, and from the late twenties on they were a loyal ally of the Soviet Union.”

After World War II, the communists won the elections in Czechoslovakia. They obtained nearly 40 percent of the vote, an unprecedented triumph. The origin of this victory lies in the Munich Convention. In line with this treaty, the Nazis had annexed a large part of Czechoslovakia. The West watched and did nothing. Bloem: “Many Czechs lost their faith in the West, and thus in democracy and capitalism. The communists put themselves forward as the true advocates of the national interest. They struck a patriotic chord and presented communism as something that matched the Czech traditions wonderfully well.”

Communism now

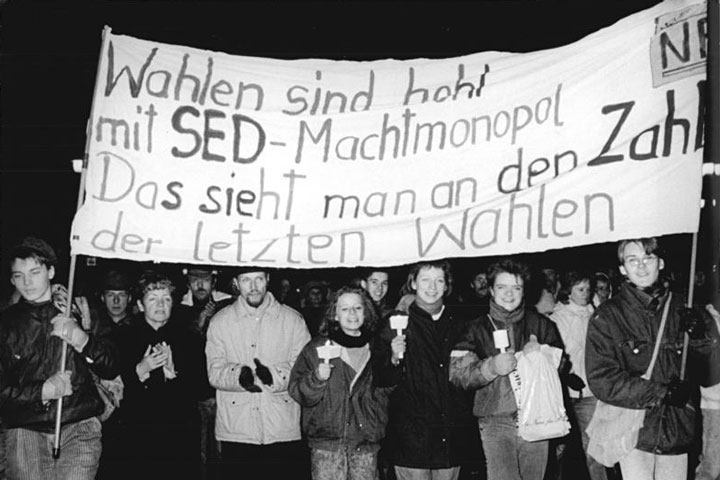

After the Fall of the Wall in 1989, the Czechs deposed the communists. The dissident Václav Havel became president and the country was finally freed from the communist yoke. However, the Communist Party was not prohibited.

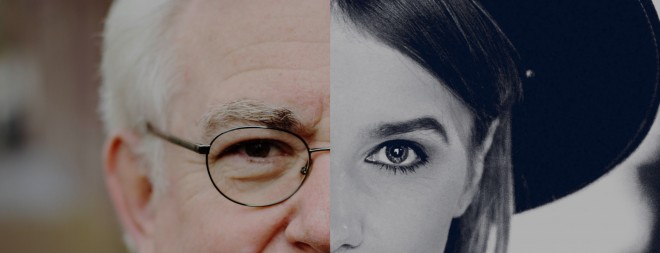

Bloem: “Havel didn’t want that. He came from an affluent family which had seen everything taken away by the communists. He did not want to do that to anyone and he thought that, to some extent, everyone had been complicit in the communist regime. Even those who had not been politically active had sustained the regime through their silence. Havel felt that the line between right and wrong did not run between different people but through each individual. He did not want to identify an entire group as wrong but called on people to look at themselves in the mirror and take responsibility for their own actions. As a result of that stance, the Communist Party managed to continue to exist.”

Reijnen adds: “People who now vote for the Communist Party often do so out of dissatisfaction with the current political climate. There is a lot of corruption in the country and a vote for the Communist Party is also a protest vote.”

Talking

Bloem and Reijnen both believe that the Czechs are gradually moving forward when it comes to facing the past. Bloem: “In the Czech Republic there is a growing amount of research into their own communist history. The archives of the Czech secret service have been made public. It is another step in the process of dealing with the past.” But the clock is ticking. Reijnen: “The Communist Party is getting older. I think it will be gone in a few years. "