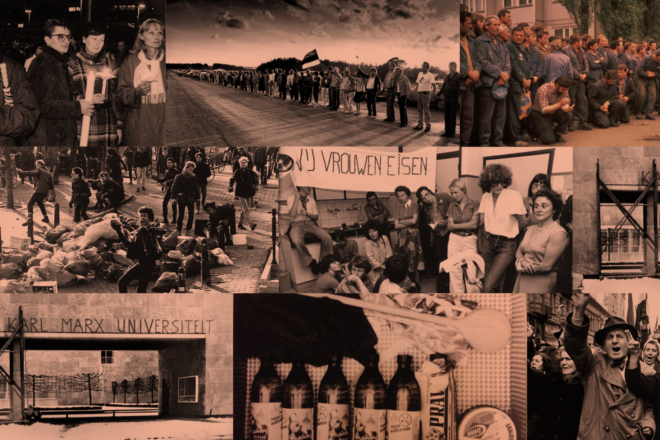

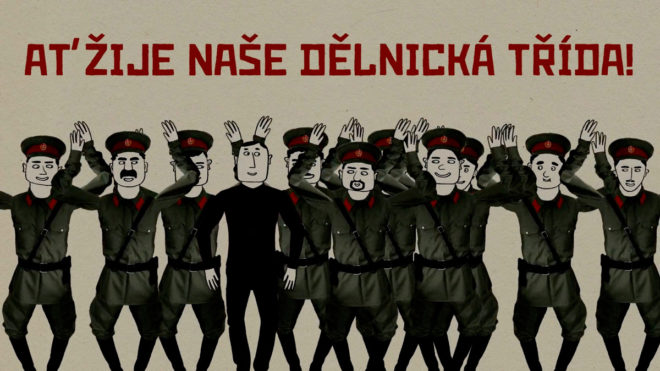

2. An opening in the barbed wire (1965-1989)

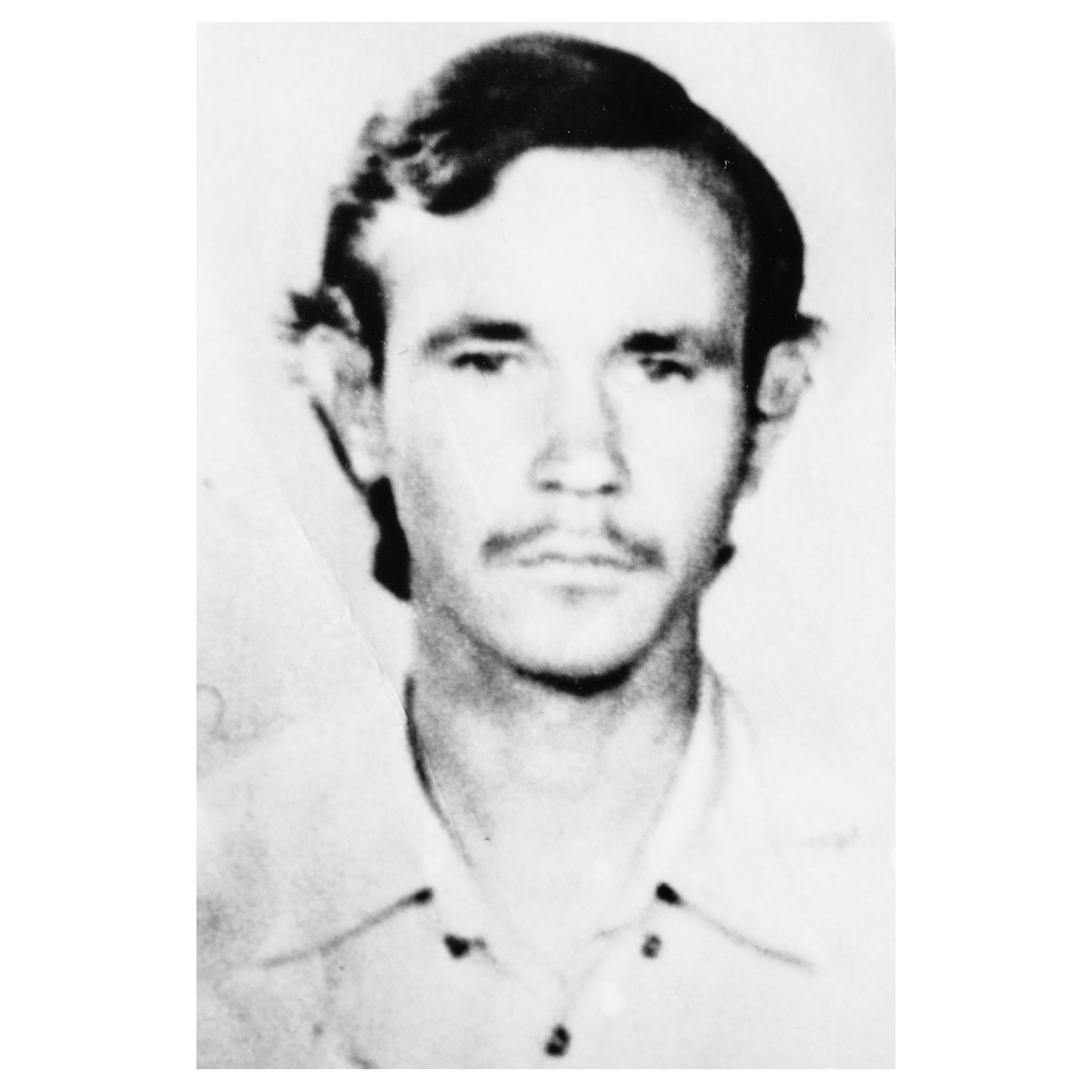

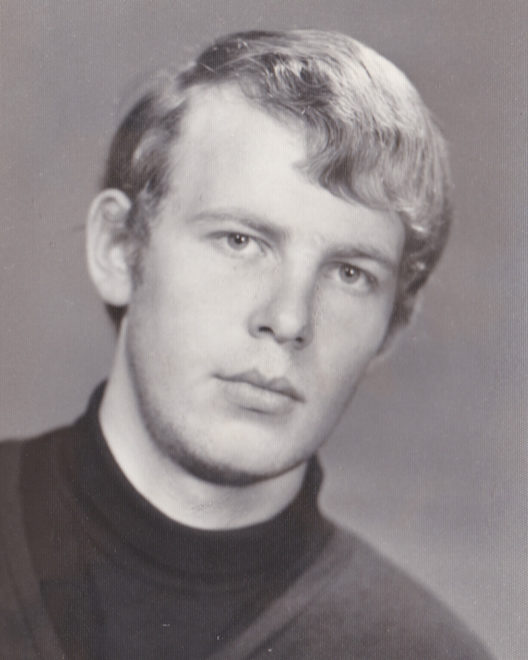

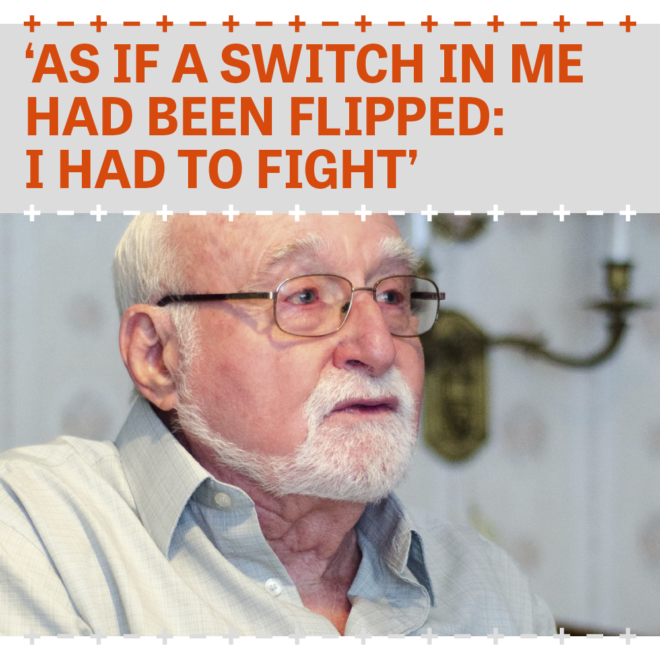

It hadn’t been Árpád’s idea, a military career in the service of the communist regime. As a 16-year-old boy, he had loved trees, flowers, and playing football outside. He had wanted to learn about biology and maybe become a gardener or forest ranger. But his best friend Joska had a better idea: they would become soldiers. Just like Joska’s older brother, who Árpád and Joska looked up to, they would get a gun and shoot. Árpád liked the sound of that. Besides: as a border guard or police officer he would also spend most of his time outside, in nature.

It didn’t take long for the first bad sign to appear. After three days of entrance tests, it turned out that Joska hadn’t been admitted. But Árpád had. The second bad omen presented itself on Árpád’s first workday. He was not allowed to go into the woods but had been assigned a post at the official border crossing. Not birds and plants but cars and asphalt would be his work domain.

Until he had to guard it, he had never even seen the border up close. Nevertheless, he knew very well what the border signified. When he was ten, he had seen how neighbours, friends of his grandparents and many others had left the country in a frenzy. They had been carrying large backpacks and were taking children his age with them. It was the autumn of 1956. In Budapest, the people had tried to start a revolution. They had taken down the statue of Stalin, and the old government was deposed. But the Russians had brutally repressed the insurgency, and now everything was dominated by fear. Many Hungarians decided to flee. Little Árpád didn’t understand everything, but he felt the panic. If those people were leaving their homes for good, things had to be better on the other side of the border.

However, at school and on the street he was told that the people in the West were bad, that they were capitalists, and wanted to invade Hungary. That’s why they needed an army and guards at the border. The country had to be protected against those evil people.

On one of his first work days, he discovered that that was a lie. His commander urged Árpád to be polite to the people from the West. After all, they were the ones who were bringing money into the country. They were not bad. They had friendly faces, drove nice cars and made small talk.

Árpád quickly understood that the barbed wire was not to protect the Hungarians but to keep them inside the communist utopia. He did what was asked of him: he followed orders.

+ - + - +

On the other side of the country, the 7-year-old Robert Molnár is standing with his grandfather in the garden of their small house. They are secretly listening to the forbidden station Radio Free Europe. The voices on the radio squeak and creak as the communist intelligence service is trying to disrupt the broadcasts. Robert leans forward and tells the forbidden world news to his hearing-impaired grandfather.

‘What do you want to be when you grow up?’ the teacher asks at school the next day. ‘A pilot,’ ‘a car mechanic,’ ‘a fireman,’ ‘a soldier,’ - the answers of Robert's classmates. ‘Prime minister,’ little Robert says resolutely. The teacher is alarmed by this answer and immediately visits Robert’s parents. What is going on with their son that he has such ambitions? Robert’s mother casts down her eyes.

His parents want Robert to keep quiet from now on, but he can’t. He is angry. His grandfather has told him how his German parents came to Kübekháza as migrants to help the tobacco production get started; through their work and that of others, Kübekháza grew into a beautiful and thriving village. However, since the arrival of the communists in the forties, the village has been completely neglected. The roads are muddy and treacherous, the houses are in disrepair, and things that are broken do not get repaired.

A few years later, when he is collecting signatures against the communist village leadership’s rule, he finds out that the communist system is far from democratic. The police arrest him and interrogate him at the station; they intimidate him and threaten to send him to a reformatory. Once outside, Robert travels as quickly as possible to Szeged, the nearest city, and joins an underground resistance movement. They have illegal meetings where they come up with protests. They create a monument commemorating the people who died in 1956 during the invasion of the Soviet troops, they read each other anti-communist poetry, and they wrap a statue of Lenin in cloth. One night, Robert travels back to Kübekháza, climbs the Soviet sculpture standing in the middle of the village square and knocks the red star off with a hammer.

On 19 August 1989, he hears on the radio that there is a breach in the Iron Curtain on the Austrian side of Hungary and that a ‘Pan-European Picnic’ is being held on that spot. He is overjoyed. It’s a sign that confirms something that he and his friends have been waiting for for so long. Sooner or later, the communist regime will come to an end.

+ - + - +

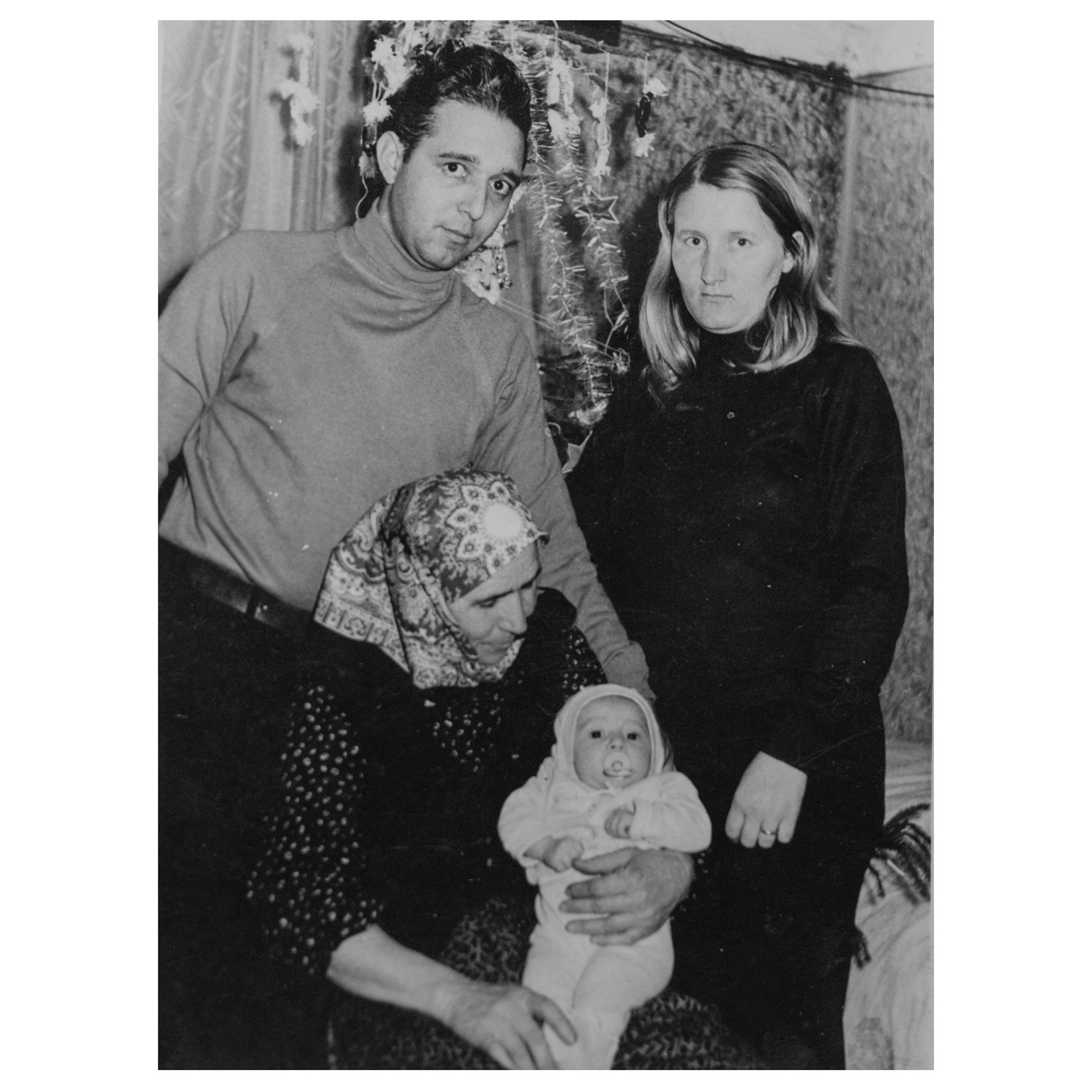

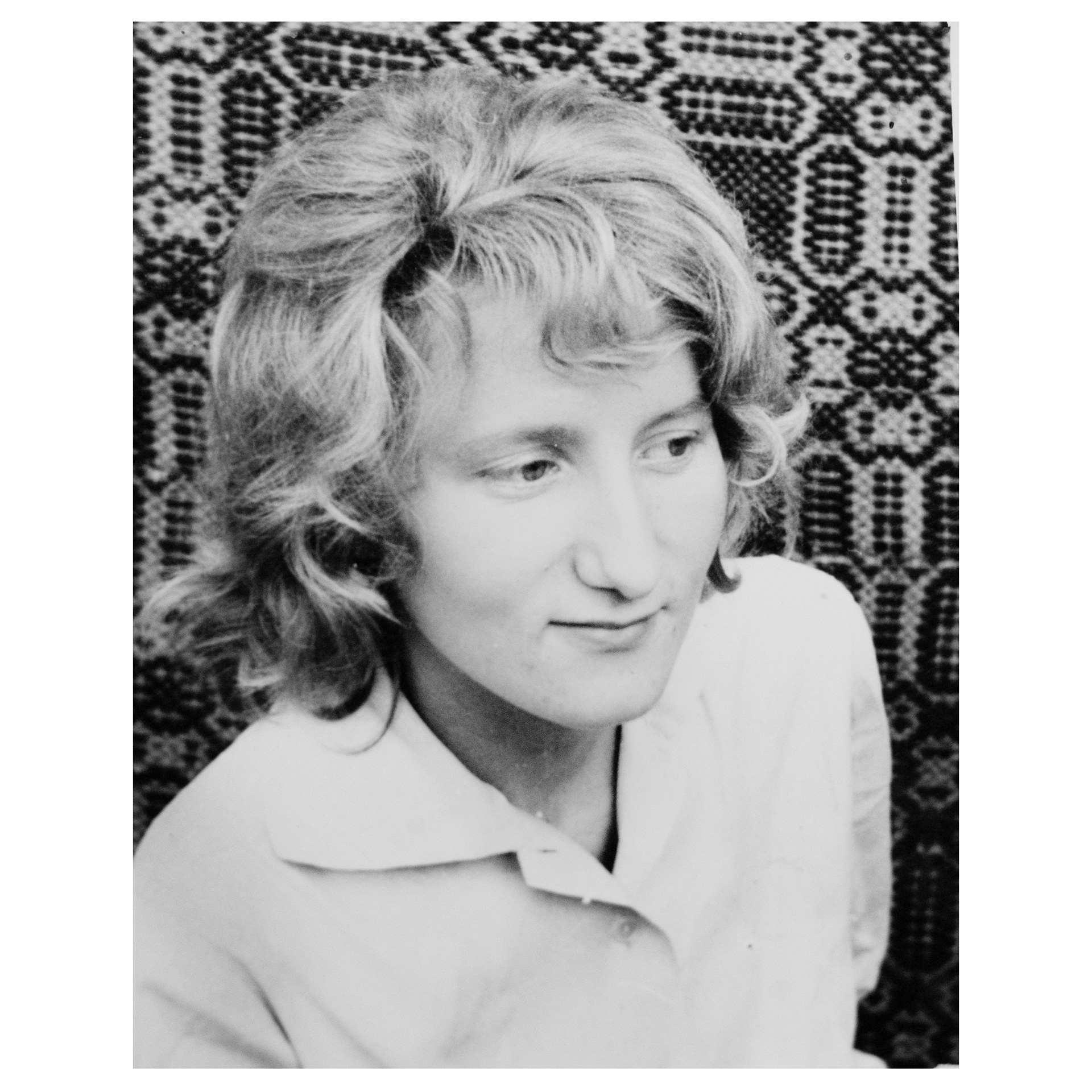

19 August 1989. In Árpád Bella's garage, he keeps a bouquet of twenty carnations. Today, it’s the twentieth wedding anniversary of Árpád and Anna, his wife. Tonight they are going to celebrate, together with their two daughters and Árpád’s and Anna’s parents. Hopefully, he will be able to leave his work on time, allowing him a long evening with his family.

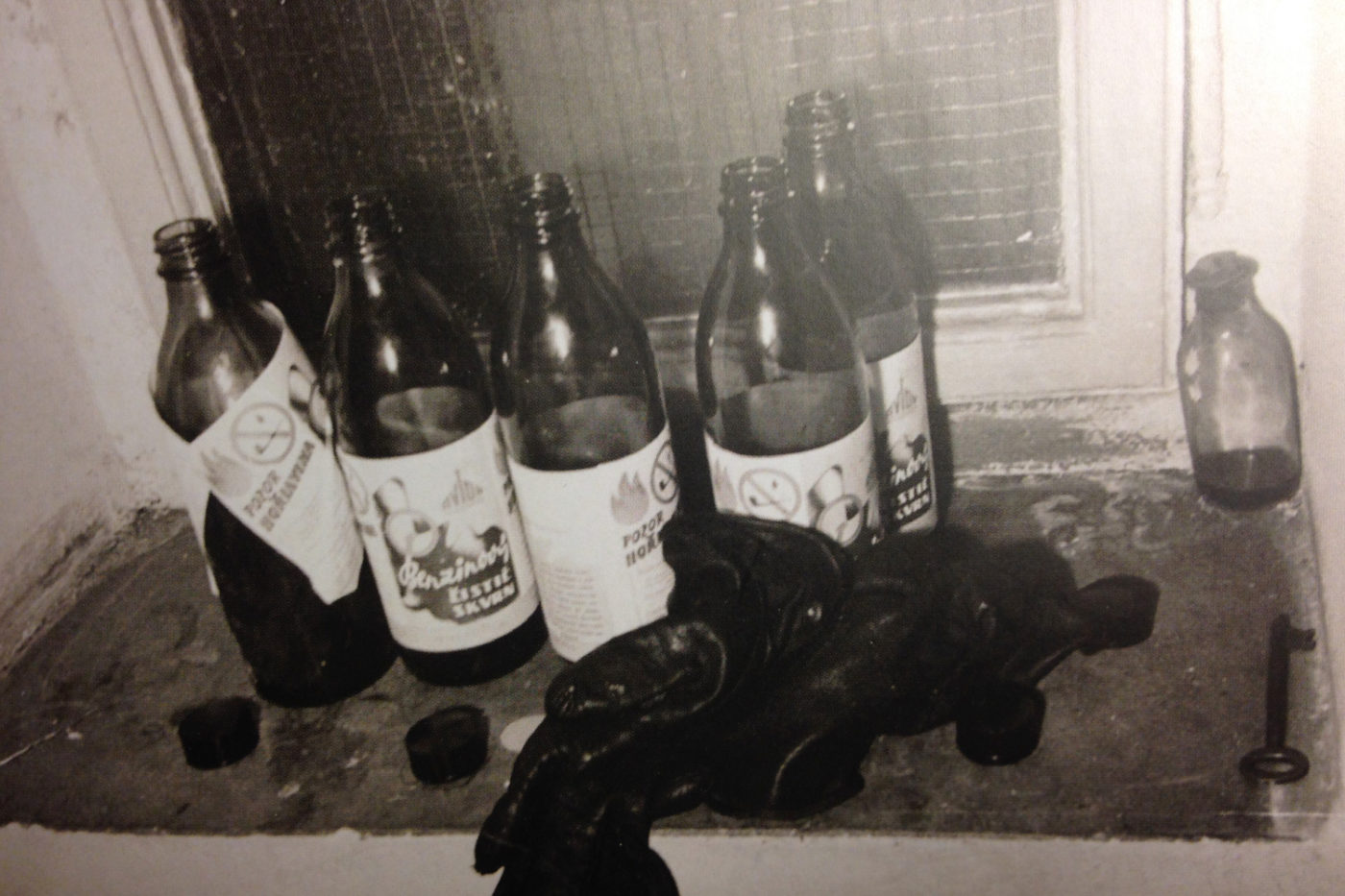

But first, work needs to be done. At Árpád’s border post an event has been planned. A ‘Pan-European Picnic’, that’s what the organisers have officially called it. It had started as a joke, just a passing thought of one of the members of the local opposition parties, which since a few months have been condoned in Hungary. A picnic on the border, where both Hungarians and Austrians can freely roast a sausage and have a drink together. As a statement. As early as 2 May 1989, the Hungarian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Gyula Horn, had cut a hole in the barbed wire on the border between Hungary and Austria, as a symbolic act. The reformist Prime Minister, Miklos Nemeth, had been clearing away the barbed wire along his country's borders for some time. It had been a practical solution: the electronic warning system wasn’t working properly anymore, and the renewal costs were much too high for the nearly bankrupt Hungary.

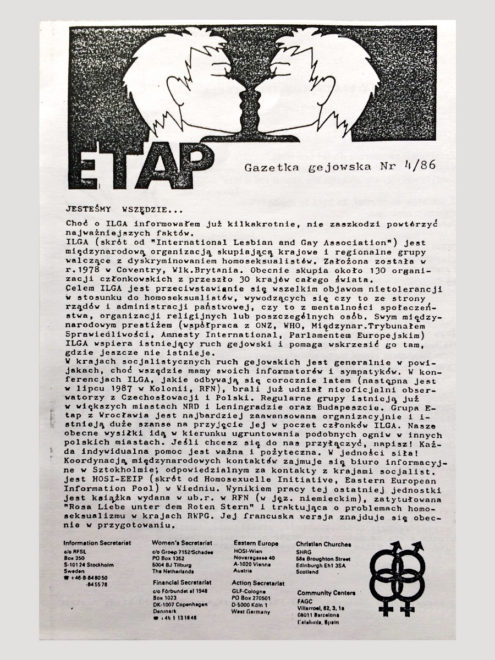

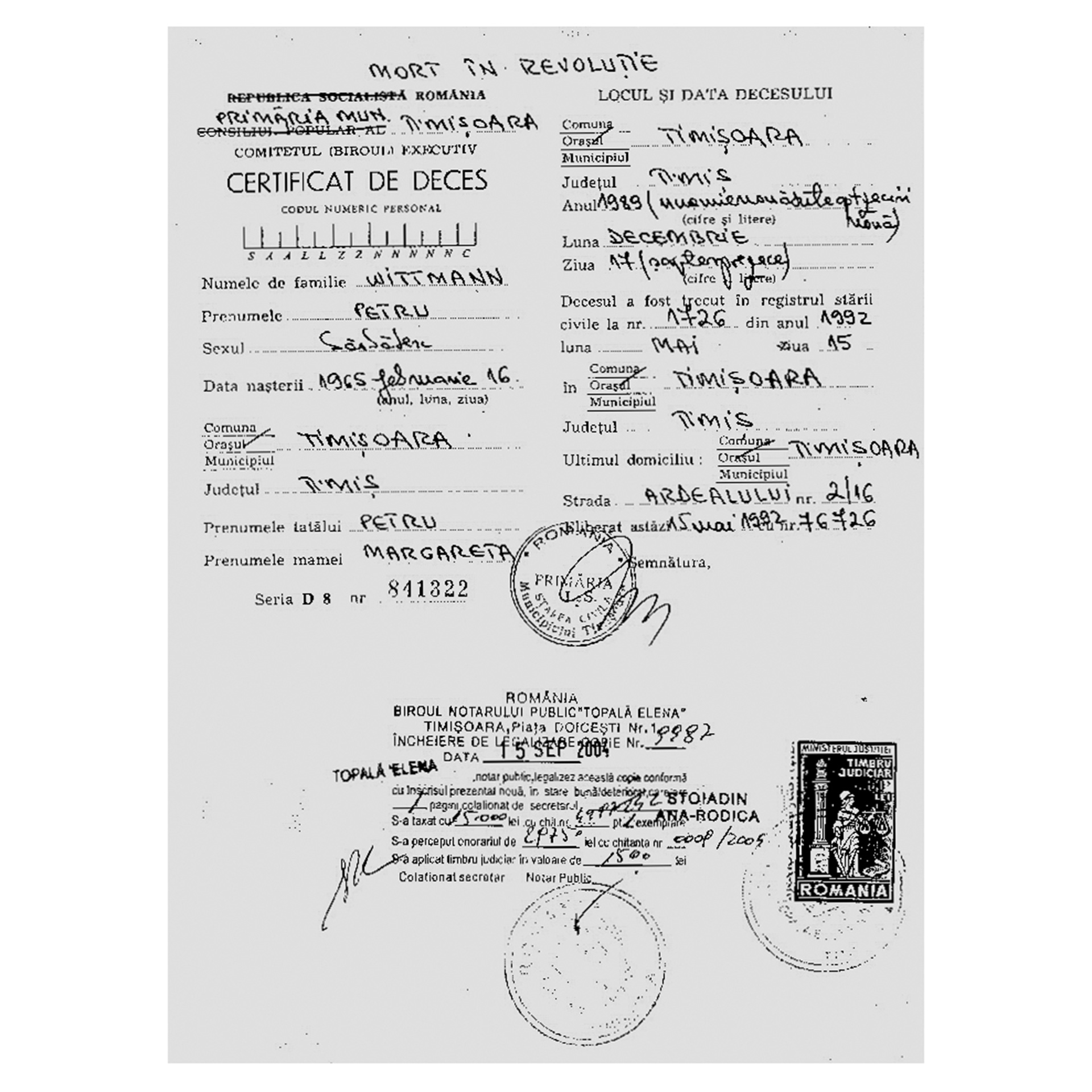

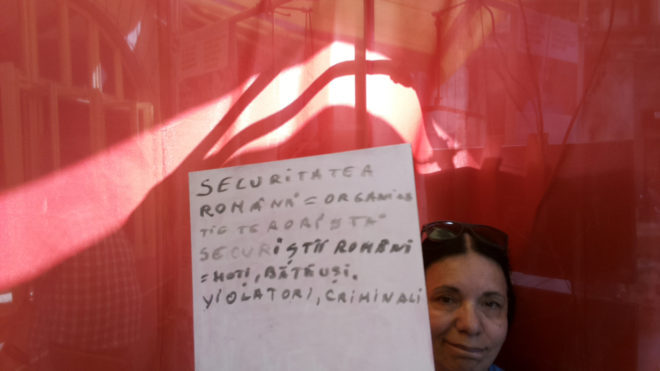

The barbed wire would not keep the Hungarians inside any longer. The quiet dismantling of the Iron Curtain didn’t make much of a difference for the Hungarian citizens: they had been given a passport in 1988, which allowed them free travel. But the opposition in the region of Sopron was indignant. The regimes in other East European countries were still as suffocating as they had been during the past twenty years. Poland was plagued by poverty, the people of Romania were terrorised by Ceausescu, tens of thousands of East Germans were trying to flee the GDR dictatorship every month. If Hungarian citizens could cross the border, why was the world keeping silent? If this was possible, why was the Berlin Wall still there? After forty years, a 280-kilometer long hole had emerged in the Iron Curtain, and nobody seemed to know or care.

And then there was something else. Wasn’t it strange that the Soviet Union had not yet intervened while the Hungarians acquired one freedom after another? The picnic organisers, a group of about twenty politically engaged enthusiasts from Sopron and the surrounding area, were worried. The Hungarian revolution of ’56, the revolt in Danzig, Poland, the Prague Spring – every attempt at reform had been violently squashed. The past had taught that you could not make it alone as a state. For that reason, the Pan-European Picnic was intended to inspire the opposition in other countries to join. The picnic would show the rest of the world that you could do whatever you wanted on the Hungarian border. Austrians and Hungarians, roasting sausages together: they would ridicule the Berlin Wall and the rest of the Iron Curtain. At least, that is what the picnic organisers were hoping for.

Árpád Bella isn’t concerned. For him, it is just another working day, and the picnic merely an item on the agenda to settle. The programme is as follows: at three in the afternoon, there will be a delegation of local dignitaries and journalists to open the border ‘officially’. Árpád is going to manage that. A permit is issued to keep the border open for three hours, exactly. At six in the evening, it will have to be closed again, and then everything will go back to normal.

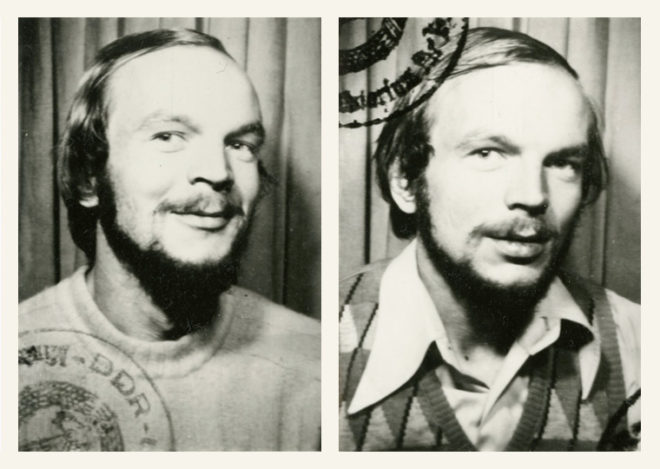

Árpád and his men collect their stamps and check the names on the delegation list. No suspicious names, no criminals - it all looks perfectly fine. Yet there is one thing that is troubling Árpád a bit: the national commander has written in a telex message that groups of people from the GDR might attempt to cross the Hungarian border. These East Germans are on holiday at Lake Balaton using a temporary visa, but they have let their travel permits expire and are refusing to go back. They might want to use Hungary to get to Austria, from where they will try to reach West Germany. In his telex message, the commander is even talking about hordes, but he writes that the government has everything under control.

Árpád has tried to obtain more information. The headquarters in Budapest, the regional commander, his colleagues in nearby villages – nobody knows anything about the East Germans. And thus Árpád does what a soldier is supposed to do: he trusts his national commander. He knows what to do.

At one o’clock in the afternoon, Árpád arrives at the border post. Strange, on the Austrian side of the borderline it’s busy already. He sees photographers, journalists, and day trippers. ‘Shouldn’t you visit Sopron for the official part with the speeches?’ he asks a group of Austrians standing at the border. He even sees a few Germans among them. ‘No,’ somebody replies. ‘We’re much more interested in what’s going to happen here.’

It’s a beautiful August day. There is nothing left for Árpád to do than to wait for the delegation to arrive. He’s enjoying the sun and talks to his colleague on the Austrian side, Johann Göltl. The two men have known each other for many years and get along very well. Johann feels considerably less relaxed; on his side of the border, it’s getting busier. Nevertheless, the mood of the waiting crowd, as well as that of the guards, is cheerful: today, it’s time to celebrate.

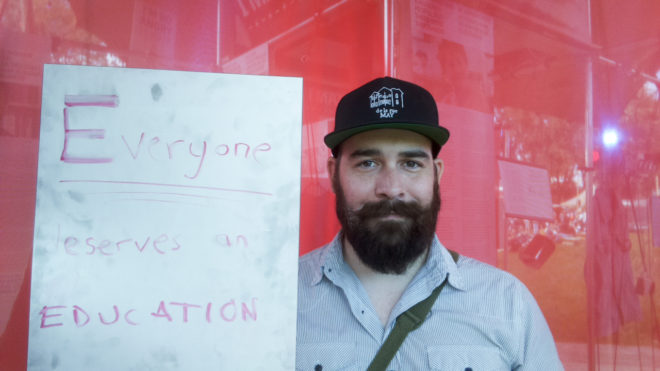

HOW TO SURVIVE A DICTATORSHIP

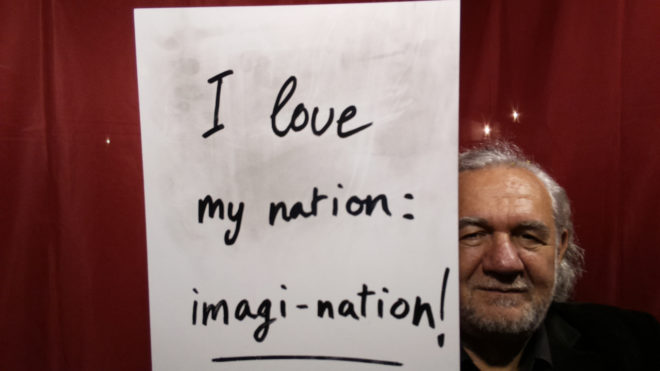

HOW TO SURVIVE A DICTATORSHIP  STRATEGY 1: Escape into your mind

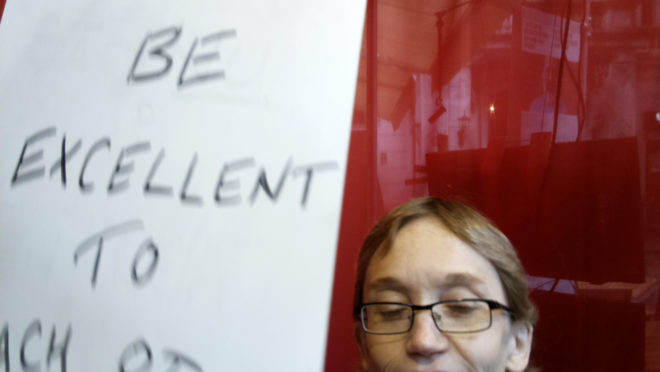

STRATEGY 1: Escape into your mind  STRATEGY 2: Be bold

STRATEGY 2: Be bold  STRATEGY 3: Trust no-one

STRATEGY 3: Trust no-one  STRATEGY 4: Grow your own vegetables

STRATEGY 4: Grow your own vegetables  STRATEGY 5: Escape!

STRATEGY 5: Escape!  STRATEGY 6: Keep the truth to yourself

STRATEGY 6: Keep the truth to yourself